Japan has been hit by investing fever

This article has been kindly reproduced with permission from The Economist and was published on 10 July 2025.

It is not difficult to spot the change. Bookshops now dedicate entire sections to financial guides. Trains are plastered with advertisements for investing seminars. Financial influencers command enormous online audiences with tutorials on how to build a portfolio or open a brokerage account. As Ponchiyo, a 31-year-old YouTuber with almost 500,000 subscribers, puts it: “People are realising it is wasteful to leave money sitting in savings.”

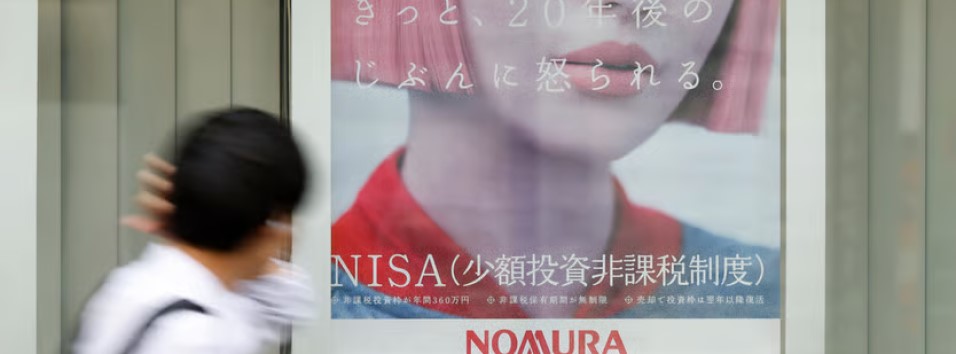

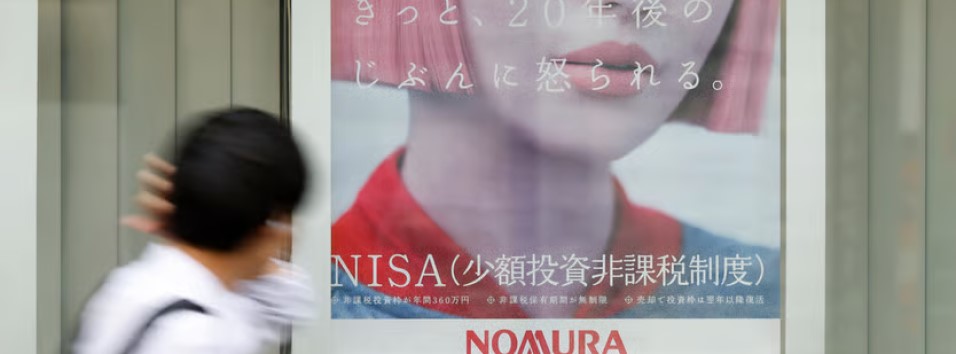

At the end of 2023, cash and bank deposits of ¥1,128trn ($7.6trn) counted for over half of Japanese household assets, compared with less than a third in Britain and an eighth in America. Then, in January 2024, the government overhauled its NISA scheme, a tax-free investing option modelled on Britain’s ISAs. The scheme has proved much more successful than ministers anticipated. Investors have opened 5m new accounts. And earlier this year, assets in NISAs reached ¥59trn, having hit the government’s target three years ahead of schedule. Japan is at a “turning point”, as Kishida Fumio, a former prime minister, put it at a recent conference. The shift is “a test of whether it can leave behind its deflationary past and embrace growth”.

After Japan’s asset-price bubble burst in the early 1990s, years of deflation and stagnation left savers wary of risk. Today, though, economic developments are creating additional incentives to invest. Japan’s core inflation has reached 3.7%, the highest in the G7, which erodes the value of idle cash, especially given the country’s relatively low interest rates. Meanwhile, Japan’s fast-ageing population has raised concerns about the durability of the pension system. “Investing used to be seen as something for people chasing big returns,” says Suzuki Mariko, who runs Kinyu Joshi (“Finance Girls”), a group for young women. “Now many people feel they have no choice but to consider it, even just to protect what they already have.”

The boom has also coincided with progress in Japan Inc. Tokyo’s stock exchange has accelerated its corporate-governance reforms as part of a broader official effort. In 2023 it instructed listed companies to “implement management that is conscious of cost of capital and stock price”. Many have responded by buying back shares, raising dividends and focusing on profitable activities; indeed, dividend payouts and share buy-backs have both reached record highs. Cross-shareholdings—used to cement corporate alliances and insulate management, often at the expense of minority shareholders—have fallen from more than 50% of publicly listed shares in the early 1990s to just 12%.

Next up: old people. Those aged 60 and over hold nearly 60% of Japan’s household assets. The government is considering a new scheme called “Platinum NISA”, which would allow those over 65 to invest tax-free in monthly dividend funds, currently excluded from NISAs, making it easier for pensioners to draw down assets. “Many seniors used to think NISA was just for young people to build their assets over a long period,” says Shiraishi Hayate of SBI Money Plaza, which runs investment seminars for retirees. “Now they are realising it can work for them.”

Not everyone is happy, however. As in Britain, critics, including local asset managers and commentators, complain that much of the money invested through NISAs is going abroad. Estimates suggest that around half of total investments go into foreign stocks, as do as many as 80-90% of those made through mutual funds. The default purchase for beginners is either America’s S&P 500 index or the Orukan, shorthand for “All Country”, a tracker of global stocks. As annoying as this may be for policymakers, neophyte Japanese investors are demonstrating wisdom beyond their years: it is never wise to be too exposed to your home market.

The articles may contain material provided by third parties derived from sources believed to be accurate at its issue date. While such material is published with necessary permission, the Westpac Group accepts no responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of, nor does it endorse any such third-party material. To the maximum extent permitted by law, we intend by this notice to exclude liability for third-party material. Further, the information provided does not take into account your personal objectives, financial situation or needs and so you should consider its appropriateness, having regard to your personal objectives, financial situation and needs before acting on it.