Tyler Cowen, the man who wants to know everything

This article has been kindly reproduced with permission from The Economist and was published on 28 February 2025.

At the end of the worst road on the impoverished Honduran island of Roatán lies Próspera, an aspiring libertarian city-state “designed for entrepreneurs to build better”. Last January Tyler Cowen, an economist at George Mason University in Virginia, found himself being ushered into an open-air co-working space beneath the attractive tropical chalet that serves as the city’s headquarters. A few digital nomads stood up to greet him, smoothing down their shorts. One of them began telling Cowen about the regulatory system in Próspera, which is partly autonomous from the Honduran government. Cowen listened politely, then looked out to where two brown birds were hovering above the shoreline. He asked what vultures were called on Roatán. Someone told him. “You use the Nahuatl word,” he replied admiringly.

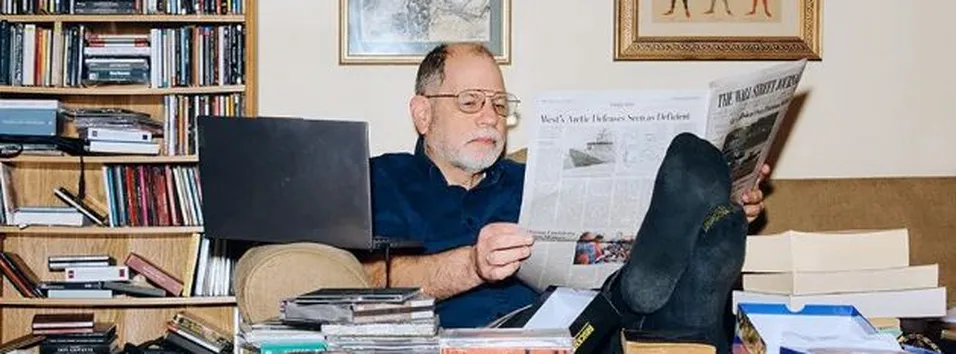

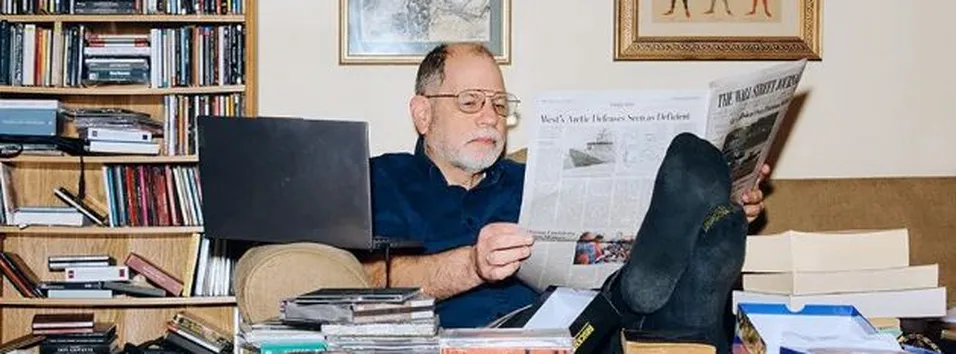

Dressed in the same tatty blue jeans he’d been wearing all week, his libertarian beard trimmed to a grey muzzle, the 61-year-old appeared before these tanned utopians as a bright star in their intellectual firmament. Cowen’s blog, Marginal Revolution, is namechecked by billionaires; his books are sold in airports and read in Washington. His grant programmes have been backed by Elon Musk, Mark Zuckerberg and Peter Thiel.

Whether they know it or not, many tech gurus now subscribe to an economic analysis that Cowen first proposed in the 2010s, when he argued that technology could rescue America from a “great stagnation” that had been keeping its growth rates depressed for almost half a century. It was this argument, amplified by his relentless publication schedule, that helped find Cowen an audience in Silicon Valley and its downstream subcultures. Today, his readers are DOGE staffers.

Yet among acolytes, Cowen is famous not for a single theory but for the broad scope of his intellect. Put simply, he seems to know something about everything: machine learning, Icelandic sagas and where to eat in Bergen, Norway. “You can have a specific and detailed discussion with him about 17th-century Irish economic thinkers, or trends in African music, or the history of nominal GDP targeting,” said Patrick Collison, co-founder of Stripe, an online-payments company. “I don’t know anyone who can engage in so many domains at the depth that he does.”

Cowen had spent the rattly drive over to Próspera peppering his hosts with questions: how did they know they really owned the land? How much did American investment treaties protect them? What was their design vision for the city? When we sat down, the atmosphere was somewhere between a pitch-meeting and a thesis defence. Reams of founderspeak floated up into the warm breeze.

Cowen’s questioning style is info-seeking, short-winded, anti-conversational. On “Conversations with Tyler”, his podcast, famous entrepreneurs often find themselves outflanked by their interviewer. “I was lucky to be able to answer as many questions as I could,” said Paul Graham, an entrepreneur whose startup incubator helped launch Airbnb, DoorDash and Reddit. Graham told me Cowen came to his home to perform the cross-examination. Afterwards Graham tried a practical joke. He handed Cowen the penis bone of a walrus – 12 inches long and without distinguishing characteristics – and asked what he thought it was. “Tyler simply answered the question as matter-of-factly as if I’d handed him a salt shaker,” Graham remembered.

In Próspera, Cowen asked questions for the entire day including, somehow, throughout a period when he was addressing a conference on longevity. How many in the audience planned to be frozen after death and await their revival by a more advanced civilisation? Were they worried about being thawed out precipitously? Did this somehow affect their views on vegetarianism?

After the talk, people crowded around Cowen excitedly. They were a recognisable type: young, ambitious and liable to describe themselves as “nerds” or “people who build things”. They spoke about the correlation between national IQ averages and socialist governments; about tech houses and co-living; about the future of embryo selection.

Looking on, I sensed a combination of eagerness and reticence among the people who had attended the talk. Some wanted to pitch to him, others to impress him with their thinking, but none knew how to talk to him. Everyone who came up to him seemingly encountered the same problem: what do you ask the man you can ask anything? In each conversation, I would watch the questioner’s thoughts catch in their throat – at which point Cowen would jump in and begin avidly interrogating his victim.

Watching him extract all this information, I often wondered about his precise motivations. Cowen is an economist and a utilitarian: he believes people do things for reasons, in response to incentives and disincentives, and that their actions have measurable ethical outcomes. Yet there is no concrete return on most of the data-accumulating he does. He has been researching, unpaid, for decades, at a rate that would put most people in hospital. “Treat Tyler like a really good GPT,” one friend of Cowen’s advised me, in a tone that lacked any trace of irony. The rise of AIs that seem to know everything and think intelligently only sharpens the philosophical question at the core of Cowen’s life: what is knowing things actually for?

“I don’t over-analyse it,” Cowen said to me, when we spoke about this. “I once said to my wife – and this was a joke – but I said something like, ‘I’m not very interested in the meaning of life, but I’m very interested in collecting information on what other people think is the meaning of life.’ And it’s not entirely a joke.”

In the early 1990s Alex Tabarrok, a graduate student in economics at George Mason University, got a job as a research assistant for Cowen, then a young professor with a wunderkind reputation. One day, Tabarrok took a paper to his boss for comments, and left it on the table. As he turned to go, Cowen stopped him. “Tyler says: ‘No no, sit down.’ And he takes the paper and he just starts turning the pages. ‘You should take a look at Arrow, 1945.’ Turns the page. ‘No, that’s wrong.’ Turns the page. ‘Oh, that’s a good point.’ He just went through my paper like it was nothing.”

Later, I sat next to him while he went through an economics paper. He read it at the speed of someone checking that the pages were correctly ordered.

Family lore holds that Cowen taught himself to read aged two. He grew up in New Jersey, and was a quiet child engrossed in baseball cards and science fiction. From an early age, he seems to have been seeking outlets for his obsessive tendencies. At ten years old, he watched Bobby Fischer beat Boris Spassky on TV and got interested in chess. Within a few years he was working as a professional chess tutor, and at 15 he became the youngest-ever state champion.

Cowen’s father was a gregarious libertarian who ran the local Chamber of Commerce. When Cowen was a young teen, he was taken to dinner with a friend of his father’s called Walter Grinder, an economist whose life revolved around constant, polymathic reading. He could talk fluently about any author Cowen could name. “I thought, ‘I want to be a more professionally successful version of that,’” Cowen remembered.

Cowen breezed through school and university at the top of the class while putting his real energy into his newest obsessions. In high school, he would take the bus into Manhattan to attend economics seminars at New York University. While still an undergraduate, he published scholarly articles in prestigious journals, but remembers the period for his immersion in classical music. He discovered art, travel, ethnic cuisine, all while pursuing a PhD – which he obtained by the age of 25. One obsession bred another. He went to Haiti, which meant he started collecting Haitian art, which meant he met an expert in the field, who also collected indigenous Mexican bark-paper paintings. That ultimately led him to the back seat of a $600 cab that took him to the tiny mountain village of San Agustín Oapan. Soon, a procession of brightly coloured dream paintings joined the Haitian voodoo motifs that decorated Cowen’s suburban house in Fairfax, Virginia.

Not long after arriving at George Mason, Cowen read “Sexual Personae” by Camille Paglia, a buccaneering polemic about Western art across millennia. Although he didn’t agree with Paglia’s ideas, he saw this was the kind of book he wanted to write. Within months he was drafting a lively, popular history of markets and high culture. In 2003 he and Tabarrok decided to start a blog called Marginal Revolution. If Tabarrok was a meat-and-potatoes libertarian – pugnacious and politically legible – Cowen was always more oblique. He might post about how protectionism hurts fine dining, or refer to the treaty of Westphalia while discussing Vermeer. The pair developed a joke: if a post made you furious, it was written by Alex; if it left you mystified, it was written by Tyler.

Few readers could have guessed that Cowen was putting together a broader vision of modern economic history. Early on in Cowen’s career, Derek Parfit, a British philosopher, had asked Cowen to write a paper with him about social-discount rates, a policy tool used to give a value to projects that deliver benefits over many years. Since future goods are less urgent and more uncertain than present ones, governments “discount” the benefits the further they come in the future.

Parfit and Cowen insisted that this leads to moral absurdities. “According to a social-discount rate of 5%, one statistical death next year counts for more than a billion deaths in 400 years,” they observed. They concluded by arguing that discount rates were not morally coherent. We should be equally concerned about the known consequences of our actions, regardless of when those consequences take place.

A standard corollary of this position is a demand for stronger action on climate change. But Cowen turned to its implications for economic growth. Crucially, the gains from growth compound with time. Failing to hit 1% GDP growth in a given year might seem unimportant. But if a country did it consistently for a hundred years, the damage would be much bigger than the sum of the annual failures. Anything that took away from GDP growth right now was in some ways taking money out of the pockets of future generations. In Cowen’s eyes, economic growth wasn’t merely desirable; it was essential.

In 2011 Cowen published a digital pamphlet in which he argued that since the 1973 oil-price shock, America had experienced a hidden crisis of lost growth that would be resolved only by the development of new technology. He called this period the “Great Stagnation”, and he proposed a cultural solution rather than an economic one: raise the social status of scientists. The ebook was such a success that it had to be rushed into print. It ended up as a rare event – a book about big ideas that became a bestseller.

Cowen acknowledged that the gains from rising GDP, when they came, would not benefit everyone. In his follow-up, “Average is Over”, he said that America was turning into two countries: one with a booming class grown affluent on the profits of tech, and one with everyone else. Those who missed out would have jobs as servants and service-providers for the ultra-rich. He called this new dispensation “hyper-meritocracy”.

In the early 2010s Cowen became aware through friends that he had many enthusiastic readers among the hyper-meritocrats of the West Coast. Cowen began travelling to San Francisco and Silicon Valley, where he was dazzled by both the people he met and the vast geysers of wealth they were creating. He met Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg, and was invited to dinner by Marc Andreessen, one of the Valley’s most influential venture capitalists. He blogged more about tech and started an interview podcast, the first episode of which was a “conversation with” Thiel. Silicon Valley may be vulnerable to bubbles and fads, but is also allergic to the complacency that quietly terrifies the restless polymath. Cowen feels the people he encountered there are the smartest he has ever met. “It’s like having lived four hours away from ancient Athens, and suddenly you can start going,” he told me.

If the period cemented his position as Silicon Valley’s favourite economist, it also changed how he thought. Up to this point, a lot of his work had been about how markets affect the average human. Now though, he reversed the emphasis and started to think about the effect that extraordinary humans could have on the market. He started a grant programme for talented people, and wrote a book with Daniel Gross, a venture capitalist, about how to spot them.

Cowen discovered something else: he was now famous. In San Francisco tech circles, he told me, he was perceived as being “the best” at the precise thing he did – which he described as arranging, absorbing and curating vast quantities of information. Cowen is not a vain man and he discussed his fame with an air of detachment. “I’m like an Alex Honnold figure,” he said, referring to an American rock climber whose daring exploits are enabled by a natural lack of adrenaline. “I don’t even know if he’s the best, but he’s the one who’s become iconic for it, right?” What he meant was that he wasn’t famous in Silicon Valley for being an economist or a polymath. He was famous for being Tyler Cowen.

On a wooden door in a side street in the Honduran city of Comayagua was a handwritten sign on a piece of paper. For five lempiras – about 20 cents – you could buy a wash. For double that price, you could buy a wash and get some paper towels to use, too. Cowen peered at it sceptically. “Is that what it costs?” he asked. “Or is that price discrimination?”

If every discipline can be considered as a system for organising raw data into usable information, economics is the subject that seems to permit the largest number of productive inputs. Cowen’s ambition is to be the person who has done the most to spread the gospel of economic thinking: how understanding incentives, demand curves and margins can help us live better and more fulfilling lives.

Certainly he has applied economic analysis to his own life with extraordinary vigour. Cowen has advice to offer about every aspect of human experience, including the very non-fungible domains of art, literature and food. Putting the search term “how to” into Cowen’s blog brings up a plethora of detailed lists explaining how to start collecting art, how to get into Indian classical music and “how to dine well in Yucatán and Quintana Roo”. Perhaps no one in history has tried harder to assess in quantitative terms that which most people only appreciate qualitatively.

The intensity with which Cowen pursues efficiency in all things can seem out of proportion to the rate of return. At the airport outside Honduras’s capital city, Tegucigalpa, he explained how he lays out his belongings the same way everywhere he goes. “That way, maybe once every five years you don’t lose your passport,” he said, as we attempted to board the wrong plane.

Flying over the country, he pressed his nose to the window and stared out at the crumpled brown mountains of the interior. At the turn of the 20th century, Honduras was the fiefdom of three international fruit companies. The state sold vast tracts of stolen land to these firms, which made empty promises to develop it. Soon, the country had a working railway system that didn’t stop in its own capital city. “They weren’t necessarily evil,” said Cowen, “but it wasn’t in their interests to develop the country.”

Proximity to the wealth and power of the United States has been a mixed blessing for Honduras. In the early 20th century America intervened repeatedly to safeguard its investments. In recent years America’s demand for cocaine has helped fuel a spectacular rise in gang violence. Poverty is persistent. Remittances from Hondurans working abroad are worth a quarter of GDP. More and more people are migrating north for a better life. In Comayagua billboards advertised “visa services” for Mexico. Cowen nodded towards them. “We know what that really means,” he said.

It was almost dusk and the shops were closing up. The houses here were colourful and decaying, with thick safety bars installed across every aperture. Tangles of rubber utility cable ran overhead like black vines. We were the only tourists in town. As we walked, Cowen hopped on and off the cratered pavement, occasionally putting on a short, surprising burst of speed to dodge oncoming traffic. He was here, he said, to understand why the drug war was hopeless, and why Honduras had been spared from civil war in recent decades, unlike its neighbours, El Salvador and Nicaragua.

I asked him if he expected answers to these questions.

“Probably not,” he said. “But it structures your thought, and it helps you get to the next question.”

In the main square, families sat around an elegant stone fountain overlooked by the Baroque cathedral. Music was playing and someone was selling pink balloons by the bandstand. A man in battered Crocs walked past, toothless, using a peeled branch as a homemade walking stick. The scene was busy and cheerful, yet fringed with desperation. “There’s some evidence”, said Cowen, “that people in Central American countries convert income into happiness more efficiently than in other places.” Shortly afterwards, a neon-pink train on rubber wheels began to ferry children round and round the square.

I asked Cowen – it is the kind of question you come to ask him – what were the criteria for a perfect Central American square. He began plucking details from the scene around us. Music, trees, a church, a fountain, children playing. “Good balloons,” he noted, looking approvingly at a balloon seller. I genuinely couldn’t tell whether he was extemporising from the available details, or indexing what he saw against a pre-existing model of what the ideal square should look like.

Cowen works best in places where the skeleton of economics presses through the soft flesh of daily life. This is one reason he spends so much time writing about restaurants: places where market mechanisms of almost textbook clarity intersect with strategic opportunities for maximising human pleasure. Cowen has published so many restaurant recommendations – his “Ethnic Dining Guide” is in its 31st edition – that he has taken to asking AIs to automate his advice. One afternoon I found him in our hotel lobby holding his iPad close to his face, asking ChatGPT, “Where would Tyler Cowen recommend getting dinner near me?” A series of fried-chicken restaurants on the other side of the island appeared. He shrugged and made a disappointed noise; it hadn’t told him anything he didn’t already know.

Some of Cowen’s theories seem to misunderstand on a fundamental level why people do things at all. Use opportunity cost to your advantage, he enjoins his reader, by scheduling a call halfway through a movie; if you don’t have to reschedule, the film wasn’t worth finishing. Desserts deliver diminishing marginal returns after the first few bites; the last 80% is just empty calories, so you can skip eating it. But for most of us, the emotional and ritual aspects of these activities are not straightforwardly extricable from the pleasures they offer. Cowen’s particular psychological makeup meant that the returns on his kind of analysis were unusually high. Yet who else is really maximising value at the movies? Or dissecting the utility of the dessert trolley?

Since 2018 Cowen has applied himself to efforts that offer even larger improvements to the general good than an excellent set of restaurant recommendations. He has dispensed millions of dollars through a grant programme known as Emergent Ventures (EV), which is designed to get money as quickly as possible to young, talented people. Applicants send Cowen a description of their plan; he invites some for an interview; if he likes their idea, they get the funds they need within a few days. This may not seem like anything new, but in the funding world EV is revolutionary. A grant from Horizon Europe, a prestigious funding programme run by the European Union, takes 273 days to come through from the close of applications.

When the pandemic hit, Cowen and Collison, the founder of Stripe, set up a separate grant programme to fund research. The pair had raised and spent millions before larger bodies managed to respond. One large grant went to Anne Wylie, who developed saliva tests for covid-19. Though Wylie was a researcher at the Yale School of Public Health, and attached to a university that had a $31bn endowment in 2020, she had to turn to Cowen for funding during the century’s deadliest public health crisis (1843 magazine approached Yale for comment but didn’t receive a response).

It was another Cowen effort that attracted interest and admiration on the West Coast. Here was a further example of something that seemed to be organised better by an intellectual super-elite, rather than slow-moving state functionaries. Intellectually, Cowen’s programme has some things in common with DOGE, but unlike Elon Musk’s brainchild, it is more interested in experimentation than tearing things down.

EV likes to emphasise its search for “moonshot” projects – high-impact ways of changing the world. Take, for example, Recidiviz, a criminal-justice non-profit that Cowen funded. It has helped free 70,000 parole-eligible people, using data tools, who would otherwise have remained under supervision. Yet if you browse the winning projects, it becomes clear that many grants were not geared towards maximising the greatest good.

Ulkar Aghayeva, a post-doc living in New York, applied for one of Cowen’s grants so she could record music she had been composing that fused classical forms with the Azerbaijani tradition. Subaita Rahman got a grant for living expenses, so she could spend a summer in a tech house in Boston. Some grants were for books that I sensed Cowen just wanted to be written so he could read them: on liberalism and the city of Madrid; on the life and work of John Milton in his context; on black holes. Cowen’s devotion to the programme, which he runs full-time, deepens the paradox of his life, whereby he seems to obsessively maximise how efficiently he can accumulate knowledge of no apparent practical use.

EV describes itself as a “low-overhead” programme, which means that most of the work is done by Cowen himself. Applications are accepted on a rolling basis. Peeking over Cowen’s shoulder in a taxi crossing the interior of Honduras, I watched them load in morale-destroying blocks of 40 or 50 messages at a time. (Cowen’s emails are themselves a labour straight out of Greek mythology. He never stops. If a stranger emails him a question on Christmas he answers it that day, probably that hour.)

Once a year, the winners of EV grants are invited to an “UnConference” in Virginia, which is designed as an intellectual petri dish for people to mingle and spawn ideas. Talks are given with no preparation and to no schedule, in randomly arranged discussion groups that you can leave whenever you please. In the evening, buses take groups out to one of Cowen’s favourite restaurants. Attendees told me he would sit at the centre of a long table of young interested people whose ambition he was helping to fire, and beam with happiness. I asked Cowen if he found that his grant programme provided him with a form of reward that was different from his other work. “I’m not sure I’m following,” he replied.

A huge amount of what Cowen did seemed to be encountering other people, and I was often unsure whether this was out of eagerness to learn from them or a more basic need for human contact. Most of Cowen’s good friends seem to be colleagues from George Mason. Some acquaintances I spoke to were in awe of Cowen, but unsure why someone hellbent on extracting value from available time had chosen to be friends with them.

“He thinks of himself as an introvert,” Bryan Caplan, Cowen’s friend of 30 years told me, “which is almost impossible to believe, given what he does, but it’s actually true. I’ve seen him when we’re at an event where he doesn’t know people. He just prefers to sit next to me.” When I asked Cowen if he had felt a lack of community in the days before the internet, he stiffened a little. He said community was an overused word. But yes, he liked things better now. In every country on Earth, there was someone he could write to and have lunch with. “I consider that an extreme privilege,” he said. “Not even billionaires have that.”

Cowen’s emotional life remains a mystery. He told me he did not experience regret. “I don’t know what the function of it is,” he said. “Is it to signal thoughtfulness? To stop you making further mistakes? It’s like revenge. I don’t understand it.” Cowen also said he didn’t understand envy or anger. He didn’t know what he should be envious of. He didn’t get lonely, by himself or in company. He actually said, “Why bother?”

When he told me he had never been depressed, I asked him to clarify what he meant. He had never been clinically depressed? Depressed for a month? For a week? An afternoon? I looked up from my notebook. An enormous smile, one I’d not seen before, had spread across the whole of Cowen’s face.

“Like, for a whole afternoon?” he asked, hugely grinning.

On our final day together, we took a taxi over thickly wooded hills to the seashore, where we were picked up from a small wooden jetty in a rusty cruiser. We were looking for lunch. As we sailed round the bay, the only building we could see was a ramshackle wooden platform that jutted out over the water.

It was only as we were pulling up alongside it, getting ready to disembark, that I noticed the banners. “FUCK TRUDEAU”, read one. “TRUMP 2024: SAVE AMERICA AGAIN”, read another. A sign above the bar stated that cash, bitcoin, gold and silver were all accepted. Two antique naval cannons sat on the deck nearby.

The man keeping bar had a long grey ponytail and a gold tooth. He was wearing a black singlet screen-printed with Donald Trump’s mugshot. He looked like he had been high since at least the first Bush administration. We took a seat and looked around. By the kitchen entrance sat a pink-faced capuchin monkey with a thin grey rope tied round its neck.

“A lot of the right has gone crazy,” Cowen had said to me earlier in the trip. He said it often, in fact. Cowen has always favoured more immigration and opposed Donald Trump. Almost the only time in his writing that it is immediately clear where Cowen sits politically is when he attempts to distance his own brand of libertarianism from what he calls the “new right”. Classic libertarianism of the Cowenian kind is a worldview built upwards from the principle of human autonomy, and traditionally endorses the legalisation of drugs, high levels of immigration and no welfare state whatsoever. It has remained a political delicacy. An ever-smaller group of true believers despair at the way the libertarian mainstream has chosen to support a narrow, rebarbative nationalism. To Cowen though, the two groups still seem like fundamentally different beasts.

Cowen began to indefatigably ask the bartender questions. What were house prices like round here? Had he closed during lockdown? Were there lockdowns in the nearby village of Jonesville? The proprietor complained about how governments everywhere had been interfering in people’s business. “But everything’s turning upside down now,” he said.

“What do you think has made the difference?” asked Cowen.

“Maybe covid did it,” said the owner. “People woke up to how these governments are trying to eliminate them.”

A trembling, wall-eyed chihuahua trotted out of the kitchen and began consorting with the monkey.

“Do the dog and the monkey get along?” asked Cowen.

“The monkey gets along with everybody,” said the barman, who now lifted it up and cradled it in his arms like a baby.

“Does the monkey bite?”

“What do you think he’s got them teeth for?”

As we came back to shore, Cowen smiled at the unremarkable, deserted village. “I’m long Jonesville,” he said warmly. (He often speaks about places and people as though they were stocks you could go long or short on.) I asked him if he would think about investing in property here. He shrugged as if to say “why bother?”

The cab had begun to grind its way up towards the brow of a hill with audible, Sisyphean difficulty. I mumbled something about whether we were going to have to get out. “We’ll make it,” Cowen said firmly. He was talking about how he liked to play basketball at a court near his house. He didn’t mind playing with other people, but most days he was the only person there. He’d been doing this for two decades now; it was an efficient form of exercise; the weather was mostly good. I asked him what he’d learned playing basketball alone for decades. “That you can do something for a long time and still not be very good at it,” he said. The car began to roll downhill

The articles may contain material provided by third parties derived from sources believed to be accurate at its issue date. While such material is published with necessary permission, the Westpac Group accepts no responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of, nor does it endorse any such third-party material. To the maximum extent permitted by law, we intend by this notice to exclude liability for third-party material. Further, the information provided does not take into account your personal objectives, financial situation or needs and so you should consider its appropriateness, having regard to your personal objectives, financial situation and needs before acting on it.