The Pushkin heist: who is stealing rare editions of Russian classics?

This article has been kindly reproduced with permission from The Economist and was published on 22 August 2025.

On an autumn day in 2023, a 49-year-old Georgian man named Mikheil Zamtaradze climbed the steps of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BNF), a complex of four gleaming glass towers at the south-eastern edge of Paris. With a buzz cut and the thick build of a security guard, he cut a somewhat anomalous figure at the library. But he was dressed to fit in among the starched shirts and reading glasses, as was his habit; this was his 40th or so visit to the BNF over six months.

The library’s security protocols are strict, but Zamtaradze swanned in with ease. He passed through a metal detector at the vault-like underground entrance, scanned his library ID card at a turnstile, strode through a set of steel doors, rode an escalator even farther underground, and was waved by a security guard through another pair of doors.

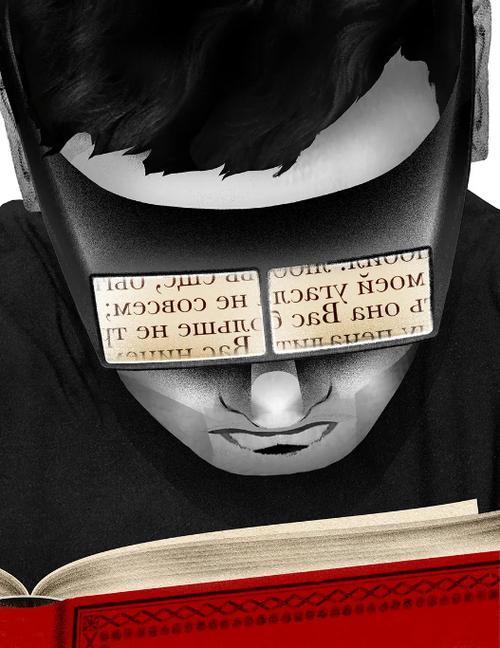

Finally, he reached the library’s rare-books reading room—a small, secluded space set apart from the clusters of stacks. Placing his open satchel onto an oak reading table, Zamtaradze asked a librarian if he could see two original first editions by Alexander Pushkin, a 19th-century writer widely considered to be Russia’s most celebrated poet. He’d consulted these volumes before, but that wasn’t out of the ordinary for a devoted scholar; he had told the library staff that he was doing research for his dissertation about democracy as a motif in 19th-century Russian literature.

After a long wait, the two books were delivered. Handling them gingerly, he placed them on an angled velour cushion, like those used for displaying diamonds. Glancing incessantly around him, he took his time leafing through the thin ivory pages, careful not to damage the books’ fragile bindings.

Zamtaradze returned to the BNF the following day. He asked to view the same two Pushkins again, but this time in a different room—one that was larger, with more nooks and crannies. But his request was denied. So he switched tactics. As Zamtaradze settled once again in the rare-books reading room, waiting for the books to arrive, he pulled out a laptop. He placed the computer—which he never turned on—on the desk, creating a barrier between himself and the librarians nearby.

Then, much to his chagrin, Zamtaradze was told that the volumes he sought were no longer available. So he packed up and left.

It turned out to be his final visit to the BNF, for the following week he was arrested at Brussels airport on a European arrest warrant. He stood accused of the theft of 17 works by Pushkin and other 19th-century Russian writers from the Vilnius University Library in Lithuania.

The contents of Zamtaradze’s suitcases did little to dispel the allegations. He had 17 books in his possession, 11 of which were forgeries of volumes that he had consulted at the BNF over the preceding months. He was also carrying fake ex-libris, or decorative bookplates, from the Pushkins that he had asked to see at the BNF a week earlier. And he had more library cards than any academic would need in a lifetime, along with a forged Belgian passport under a pseudonym.

A month later, in November 2023, French investigators received a call from the BNF’s director of collections. Following Zamtaradze’s arrest, the library had discovered that nine of the works he had consulted during his visits had disappeared. Remarkably, the texts had been replaced with facsimiles of such high quality—the paper perfectly aged, the covers carefully distressed, a rendering of the BNF’s stamp in just the right place—that only a rare-books specialist with a background in Russian literature might have noticed anything amiss.

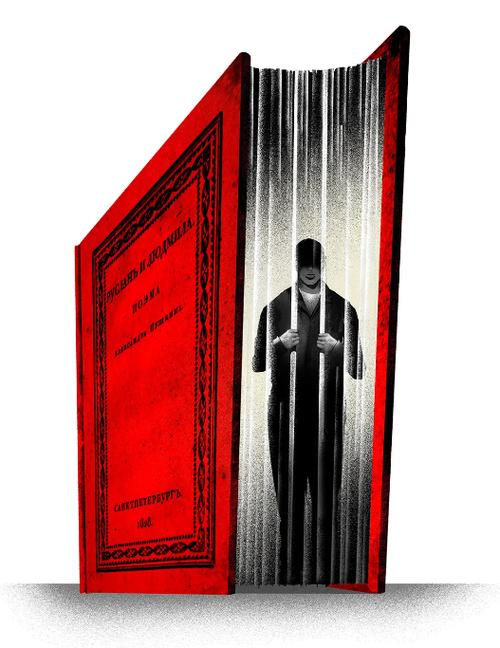

Between April 2022 and November 2023, as many as 170 first editions of the works of some of Russia’s greatest 19th-century writers—above all by Pushkin, but also by Mikhail Lermontov, Nikolai Gogol and others—were stolen from national and university libraries across Europe. In addition to the libraries in Paris and Vilnius, institutions in Berlin, Geneva, Helsinki, Lyon, Munich, Prague, Riga, Tallinn, Vienna and Warsaw were targeted. Most of the books were replaced by fakes, some of astonishingly good quality.

French police described Zamtaradze as just one node in a “well-structured, organised and itinerant” web of Georgian criminals who orchestrated every aspect of the thefts, from scouting libraries to spiriting away the original texts. For many European investigators, this was the most audacious series of book thefts they could remember—yet the thieves’ clever methods were only the outermost layer of intrigue in these continent-spanning heists.

In September 2022 whispers began to circulate among the staff of some of Europe’s most prominent libraries about a curious theft. At a conference in Vienna, a librarian from the National Library of Latvia, in Riga, revealed that in April that year, three Russian first editions had been stolen by someone pretending to be a Ukrainian war refugee; the man claimed he was interested in studying Russian literature in graduate school. “I think that’s why the librarians were so trustful of them,” Laura Bellen, an Estonian prosecutor, told me, “because they had a pretty good story of why they wanted to see those books and learn about them.”

Little else was known until November 2022, when a 46-year-old Georgian man named Beqa Tsirekidze was arrested in Riga. Shown in surveillance footage to be balding, with a rough beard, substantial belly and piercing blue eyes, Tsirekidze was convicted as an accomplice in the Latvian theft and sentenced to six months in jail.

Initially, the crime was thought to be an isolated incident. But a chance DNA match in an inter-European database soon revealed that Tsirekidze had also been the principal thief behind the disappearance of eight books from the University of Tartu, in southern Estonia. Tsirekidze appears to have carried out this theft just a day before the one in Latvia, though his ruse was discovered only by chance months later, when a reader opened several Pushkin and Gogol volumes and found something strange: stuffed into the original leather or paper bindings were pages from early 19th-century books that were in German, rather than Russian. It appeared that Tsirekidze had arranged for the creation of high-quality facsimiles using historical materials.

After Tsirekidze finished his sentence in Latvia, he was extradited to Estonia. The judge who heard his case there remarked that he had developed his criminal skills to “near perfection” and sentenced him to two years in prison (he is still serving his term). For Bellen, the lead prosecutor, this was a win, but she suspected that there were more details to uncover. “Even if I didn’t know about any criminal cases from the other countries, I would still think it’s stupid to think it’s just the two of them,” she said, referring to Tsirekidze and an accomplice (who has been identified but remains at large).

Over the next year, European prosecutors began to discover more thefts and share information through a joint investigation. At least ten other members from Tsirekidze’s organised-crime network—some of whom were his family members—were identified. Archil Tkeshelashvili, the head of Georgia’s prosecutorial investigations unit, told me that the members “had different functions allocated among themselves”. One was thought to be an expert in book forgery; another was a pro at making fake ID cards, which the thieves used to register at libraries.

The thieves would first do reconnaissance, taking photos of their potential quarry for senior members to appraise. They would relay this information, along with other messages, during frequent cigarette breaks. On one such occasion, Zamtaradze, the thief at the BNF, was caught by a surveillance camera shooting off texts to a more skittish colleague: “Most important is to stay calm. Don’t get worried, and don’t let anyone notice that you’re worried.” (These constant interruptions aroused the suspicions of some librarians, who found them unusual for supposedly dedicated scholars.)

Once their targets were confirmed, the thieves would re-enter the library—typically in pairs. “One of them would distract the library personnel, so the other had the opportunity to remove the identifying barcode from the books,” said Tkeshelashvili. Sometimes they returned several days in a row, or many times over the course of months, to obtain enough details about the volume to send to the forgery artist, or to wait for a third thief to whom they could hand off the original books or pages after they were stolen. Back in their hotel rooms, the thieves would add finishing touches to the facsimiles using tools that they had stashed in their suitcases: needles, thread, scraps of old book bindings, specialty adhesives, fake library stamps and distressed pages from other 19th-century texts.

The smuggling operations themselves required composure, co-ordination and cunning. The thieves exploited the security at the University of Warsaw’s library by wearing custom-made jackets with inside pockets so that they could easily take original pages out and bring facsimile pages in (ultimately, they succeeded in stealing 79 volumes, the most of any affected library). The BNF, as a national library, has more stringent measures in place—it requires an application and security clearance to obtain an ID—so even more ingenuity was necessary. According to a legal complaint filed by the BNF, on the days the thieves had designated for page swaps, Zamtaradze visited the library with what appeared to be a broken arm; inside the sling, there was a space into which he could slip the stolen pages.

The only time the group seems to have deviated from their careful planning was in October 2023, at a small university library in Paris. Two young thieves—one of whom was Tsirekidze’s son, Mate—began the operation as usual: after scoping out the library, they gave the staff a list of Pushkin volumes that they wanted to view.

Their selection put Aglaé Achechova on high alert. Now head of the library’s Russian division, Achechova used to work at the National Pushkin Museum in St Petersburg. She recognised the men’s list as “all the books that we always had on display during all the exhibitions at the museum”, she told me—first editions that were printed during Pushkin’s lifetime, and therefore of special interest to collectors.

For whatever reason—perhaps motivated by youthful impulsivity, perhaps by outside pressure—the two men were desperate to obtain this list of books. One night, they broke into the library, only to find that the collection’s most valuable items had already been locked in a safe box. They walked away without the loot they sought.

For librarians and law enforcement alike, this aborted robbery further entrenched suspicion that the Georgians were pursuing rare Russian classics not on their own initiative, but rather at the behest of some shadowy client. The French police thought that the heists might be part of a “project on a grander scale”, seeking to “repatriate precious objects of value to Russian patrimony and identity”. As Bellen, the Estonian prosecutor, put it, “This wasn’t just a random list of books. Definitely there was somebody who most likely ordered or said that they would be interested.” Bartosz Jandy, a Polish prosecutor investigating the thefts from the University of Warsaw, told me bluntly: “As far as the [group’s] MO is concerned, it’s typical organised crime. The only mystery here is who orders those books. And unfortunately, it matches the profile of the methods of the Russian Federation.”

Pushkin is to Russia what Shakespeare is to England, Goethe is to Germany, Dante is to Italy—a national genius. In his short life (he died aged just 37), he wrote scores of poems, as well as plays, novels and fairy tales in verse. With literary triumphs such as the epic love story “Eugene Onegin” and the political drama “Boris Godunov”, he established himself as the father of Russian literature. To this day, Russians speak about him with reverence, and many hold strong sentimental attachments to his work dating back to childhood. Reading the fairy tales that Pushkin wrote, and being taught his poems by heart at home or in school, “are very tender, intimate memories within educated families”, Achechova told me.

Pushkin was born in 1799 to a noble family in Moscow and educated in French, as was typical for the Russian gentry at the time. As a young man, he condemned serfdom and sympathised with Enlightenment ideals—including the ones espoused by a circle of liberal military officers, aristocrats and intelligentsia who in 1825 would go on to stage the unsuccessful Decembrist revolt against the autocratic tsarist regime. He was not quite 21 years old when his political poetry landed him in his first exile, to the provinces of the Russian Empire—which was then nearly at its height, stretching from Poland in the west to Siberia in the east. Whereas other Russian writers and thinkers of the time sought to emulate Western literary genres and styles, Pushkin drew from the vernacular he heard at provincial marketplaces and country estates, creating a poetic language that could be understood not just by aristocrats, but by the wider public. Before Pushkin, Russian “was just crude”, Ewa Thompson, a scholar at Rice University, told me. “To read an 18th-century poem, and then read Pushkin—it’s a different language, almost a different world.”

As Pushkin shuffled in and out of exile, he sometimes supported the Russian government in his writing and sometimes satirised it. “The Russians like to think of Pushkin as a writer who waged battles with the tsarist regime, as a writer who was a victim of political censorship, and he was in some ways,” Edyta Bojanowska, a professor of Slavic studies at Yale University, told me. But when it came to “Russia’s bold imperial posture” at the time, she said, “There was also a lot that he agreed with.”

Russia’s wars and colonial conquests appear frequently in Pushkin’s work. His travelogues, such as “A Journey to Arzrum”—which chronicles his trip through the Caucasus and eastern Turkey amid one of Russia’s brutal military campaigns in the region—“suggest[s] that Russia is a benevolent agent bestowing order and identity on primeval chaos”, Thompson argues. A few years later, in 1831, Pushkin wrote the poem “To the Slanderers of Russia” in support of the violent suppression of a rebellion in Poland by Russian troops. “Slanderers” is published in all editions of Pushkin’s collected works, and “Pushkin himself thought it was hugely important,” Bojanowska told me. And yet it is rarely included in curriculums, even in the West. “It’s kind of like this dirty little secret,” she said.

Russian literature never had the broad post-colonial awakening, or at least the critical distance, that came about in French or British literary studies. This is in part due to the unique formation of the Russian Empire: unlike France or Britain, Russia “acquired its imperial territories almost exclusively by adjacence”, the post-colonial theorist Edward Said has written. As a result, some intellectuals (including Pushkin) conceived of conflict between Slavic nations and cultures as a “family matter”—an expedient political shibboleth that also made its way into academia. These ideas hindered modern scholars from interpreting Pushkin’s work as a tool or emblem of Russia’s imperial ambitions.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 has accelerated the work of some academics to re-evaluate the work of Pushkin and his peers in a post-colonial context—trying, as Bojanowska put it, “to make visible their imperial entanglements”. Meanwhile, Russia has been waging a cultural battle in parallel with its territorial one, using Pushkin’s image in the occupied territories as a symbol of the eternal greatness of its language and culture. After bombing Mariupol’s grand theatre while civilians were sheltering there, Russian forces draped the destroyed façade with portraits of Russian playwrights and authors, including Pushkin; in Kherson, they have put up billboards plastered with Pushkin’s face, declaring that Russia was “here for ever”. His work, too, has been used to try to justify the war, with the foreign minister Sergei Lavrov reciting “Slanderers” in a video clip for Russia’s Channel 1, which was overlaid with menacing images of European Union officials and President Joe Biden.

On a balmy April afternoon, in a neighbourhood in northern Tbilisi festooned with oriental plane trees, I joined a dozen people in a small, airless courtroom with salmon-coloured walls. At approximately 5pm, a cluster of police accompanied Mate and Kristine Tsirekidze, Beqa Tsirekidze’s 20-something son and daughter, into the room. Mate, stocky and wearing a Los Angeles Lakers jersey, had unkempt bronze-coloured hair and the same blue eyes I’d seen in photos of his father. He sat down in a glass box between two security guards and leaned indifferently against the wooden banister, winking at his sister, who was seated at a table wearing a black tracksuit jacket, her long hair in a messy half-bun. As the hearing went on Kristine periodically turned towards the gallery and smiled in amusement at her family, at one point pulling her fingers across her lips in a zipping gesture.

The Tsirekidze siblings seemed awfully juvenile, surprisingly nonchalant and even naive—hardly the sophisticated operators one might expect to be behind the book thefts. And yet they had been rounded up in April 2024, as part of a joint investigation by Georgia and several European countries. On a single day that month, a hundred law-enforcement officers conducted searches in 27 locations across Georgia and Latvia, recovering 150 stolen books. Disappointingly, most were not the original library volumes and were instead “extra” texts, perhaps used to make facsimiles.

Even so, Georgian investigators had enough evidence passed along by their European counterparts to bring four members of the Tsirekidze gang—including Mate and Kristine—to trial. (French police had also found Mate’s DNA at the break-in at the smaller library in Paris.) The day I saw them, the siblings were in court for an appeal hearing—the outcome of which was the scheduling of yet another hearing (both Mate and Kristine have denied committing the thefts).

Given that all the thieves are Georgian citizens, and have brought at least some of their spoils into Georgian territory, the country’s prosecutor’s office has now taken on the responsibility of locating the remaining stolen volumes. Its investigation has revealed the extent to which the Tsirekidze gang—despite their unusually resourceful methods—is a fairly typical Georgian crime ring, running a fairly routine smuggling operation.

Georgia, which was once part of both the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union, is a hub for organised crime; its mafias control much of the criminal activity in the Russian-speaking world (though they are usually associated with less genteel lines of business than books, such as drugs and money-laundering). One of the most notorious clans hails from the ancient city of Kutaisi, which is also the hometown of the Tsirekidze family. Beqa Tsirekidze and Mikheil Zamtaradze, who are believed to have headed the book-thieving organisation, have classic rap sheets for gangsters: Tsirekidze has charges of theft and purchase of stolen property on his record, while Zamtaradze has faced fraud charges. Both also have eyebrow-raising backgrounds in “antiques dealing”.

The commonplace character of the gang was further impressed upon me a few days later, when I hired a taxi to go to Mtskhetisjvari—a village an hour and a half north-west of Tbilisi where, during the joint investigative operation last spring, investigators found three books that had been stolen from the BNF. According to Georgian legend, Mtskhetisjvari is a good place to stash valuable items: it is named after the cross of Mtskheta, a sacred wooden relic that was supposedly hidden there by Georgians in the 10th century to protect it from Muslim invaders.

“Remote” doesn’t do justice to the village. It is home to fewer than 100 people and consists of one paved road and a scattering of gravel paths, along which sit a handful of homes cobbled together from stone, brick and aluminium. The only public spaces are a Soviet-era cultural centre, now fallen into disrepair and filled with wooden detritus, and a pristine football pitch, set amid dazzling green countryside.

My translator and I wandered around for a while, knocking at front gates and asking the few residents we met if we were in the right place. Finally, a man came out from an enclosed yard, stopping in front of a silver VW Passat with French plates. He was dressed in black shorts and a T-shirt, with rosary beads wound around his neck and wrist. He told us that his daughter was married to Besik Akhalashvili, who had been arrested after the BNF books had been found stashed in a bedroom during the raid. (Later, Akhalashvili was determined to be Mate Tsirekidze’s accomplice in the break-in at the university library in Paris.)

“If I’d known [Akhalashvili] was a criminal he wouldn’t have been allowed in the house,” the man said. “He seemed to be a good kid though. No alcohol, no drugs, always ready to help.” His daughter was still in love, he said, and had become depressed since her husband’s arrest.

The man didn’t have any insights into how Akhalashvili had joined Tsirekidze’s network; he lived most of the year in France, where his wife was receiving medical treatment, and from where he arranged for the import of foreign cars into Georgia.

Georgia, at the intersection of Asia and Europe, has always been an important avenue for trade. During the latter days of the Soviet Union, its rugged and porous borders supported extensive smuggling in Western goods. The route has become only more lucrative as sanctions have hit Russia; car exports from Georgia, for instance, have doubled since 2021, with Porsches, Maybachs and Lamborghinis making their way from various European countries to Moscow showrooms via the Caucasus. A few years ago some clients apparently began signalling to Georgian gangs that something else had caught their eye: rare books.

Today, rich Russian art connoisseurs face a conundrum: they have money to spend, yet limited places to spend it. Sanctions have curtailed their ability to buy things from abroad, and Western dealers and auction houses are cut off from the Russian market. According to Ekaterina Nikolaeva-Tendil, a Russian art expert based in Paris, the invasion of Ukraine in 2022 created “two separate [art] markets: one in Russia, and one in Europe”.

There has since been a surge in interest among domestic buyers in traditional Russian art: religious iconography, paintings of rural life, and other works that stoke national pride or have some historical value. “The moment the invasion started, all the nationalist artists were shown,” James Butterwick, a British art dealer, told me. “Most of it is monumental crap, but it promotes the message that Russia is in some way different from the rest of the universe.”

The sector has been growing as Russia’s geopolitical ambitions have become more brazen—with rare books rising with the tide. In an interview in 2014, Sergey Burmistrov, the founder of Litfund, a prominent auction house in Moscow, remarked that “few people in the West are interested in Russian books” but that there was burgeoning interest inside Russia following the annexation of Crimea that year. “Prices in this market will grow,” he said, adding that a book is “the best gift”. Burmistrov also observed that the provenance of an edition affected its price: “Books from famous private libraries of the past are in great demand.” (A few years later, in November 2021, Beqa Tsirekidze appears to have arrived in the Baltics to begin scouting for rare books at some of Europe’s best-known libraries.)

The works of Pushkin in particular serve as a status symbol—a demonstration of one’s wealth, erudition and nationalist bona fides. First editions are rare, but not one-of-a-kind; “They cost a lot but they exist” in Russia, Nikolaeva-Tendil said. The stolen copies might not be in perfect condition after years in a library, but “to find a Pushkin, lightly damaged, at a lower cost, it might be worth it” to complete a collection. Achechova, the librarian in Paris, told me that the editor-in-chief of an important Russian newspaper had once bragged in an interview that he owned original copies of every Pushkin volume ever published. “For collectors, having an original Pushkin, it’s a must,” she said.

Those investigating the library thefts had reason to believe, however, that a handful of rich collectors weren’t the only ones driving the demand for rare Pushkins. Indeed, the cultural significance of the stolen books, and the scope of the Georgian gang’s smuggling operation, initially stirred speculation that the Russian state itself was involved. That theory “seemed reasonable”, Tkeshelashvili, the Georgian prosecutor, said.

There is some precedent. Since the annexation of Crimea, a clutch of government groups—including the Ministry of Culture, the Federal Security Service (FSB), and the Russian Historical Society (whose chairman is Sergei Naryshkin, the head of the Foreign Intelligence Service)—have allegedly abetted the theft of cultural artefacts from abroad. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has allowed its forces to transfer objects like stone-age sculptures and gold Scythian decorative works out of annexed territories with impunity. One exhibition recently staged inside Russia, in Veliky Novgorod, displayed 200 objects taken from Crimea that touted the “grandeur of the [region’s] churches”.

The Russian state often outsources grubby tasks to organised-crime groups. The British scholar Mark Galeotti has shown how the smuggling networks that sprang up during the 1980s to fulfil the Soviet Union’s insatiable demand for Western goods evolved in the 1990s into full-fledged gangs, often with ties to Russia’s security services. Over the next three decades European intelligence agencies recorded many cases in which criminals were induced to perform tasks for the Russian state, ranging from the production of counterfeit cigarettes (the proceeds of which funded Russian intelligence operations) to assassinations on foreign soil.

This illicit activity became more pronounced once sanctions began to be imposed on the country in 2014. But with the invasion of Ukraine, Russia “shifted into a full ‘mobilisation state’”, writes Galeotti, “in which all elements of society—illegal as well as legal—are expected to play their full part in the war”. Organised crime was tasked with supplying new means to dodge sanctions. For instance, European customs officials noted that the sales of refrigerators from the EU to Kazakhstan tripled in 2022; microchips from these “smart appliances” have since been found in Russian missiles and drones. As one British intelligence officer told Galeotti in 2023, “Crime is the magic answer to so many of [Vladimir] Putin’s problems.”

In recent months, Georgian prosecutors have moved away from the theory that the Russian state is behind the book thefts, citing a lack of evidence. But though it is unlikely that anyone in Putin’s inner circle ordered the thefts, that doesn’t mean that lesser officials haven’t benefited from the Tsirekidze gang’s entrepreneurship.

Last year, on a bleak winter morning, I went to Warsaw to meet Bartosz Jandy, the Polish prosecutor who is handling the investigation into the thefts from the University of Warsaw library. A brawny, jovial man in his mid-40s, he was wearing a checked shirt and drinking coffee from a “Jurassic Park” mug when we met in his office overlooking the Polish Ministry of National Defence (he works for the Polish army, but is leading the stolen-books investigation because civilian courts are overburdened).

Jandy beckoned me to look over his shoulder at his computer screen, where he pulled up the website for Litfund, the auction house owned by Sergey Burmistrov. Scrolling through the offerings, he stopped at photos of a three-volume set of the collected works of Aleksander Radishchev, a radical Russian writer from the late 18th century who was, like Pushkin, exiled for condemning serfdom.

The books came from the University of Warsaw’s collection, Jandy said. They had once featured traceable barcodes, which had been scratched off, as well as the library’s blue stamp, which was still faintly visible. “You see, they wanted to have a complete item,” Jandy observed. The set had sold for 5.5m roubles (around $50,000)—a tidy sum for obscure volumes.

Jandy noted that Burmistrov had links to the Russian government: he has worked as an expert at the Ministry of Culture. And Burmistrov once again seems keen to laud the nationalist value of his work in public. Last summer, in an op-ed for Forbes Russia, he weighed in on “the European thefts that are currently on everyone’s lips”, as he put it. “Pushkin is our everything,” he gushed, before denying that Russians or the Russian state were involved in the thefts: “This is not a special operation to export Russian books from Europe.” Yet he seemed to admonish the libraries for their weak security—a symptom, he implied, of the disregard Europeans had for Russian culture. Burmistrov concluded that “There is not a single collector in Russia—at least, I don’t know any—who would want to deal with rare books if they have the seals of active libraries.” Not once did he mention the allegedly stolen volumes that his own auction house had sold.

When contacted for this article, Burmistrov again criticised the security procedures at European libraries. Citing the chronic neglect of Russian collections by Western institutions, he argued that the book thefts “actually look like a ‘special operation’ of local management to destroy the departments of libraries that possess valuable Russian books”. Regarding Litfund, he said that its work is “fully transparent” and that booksellers are required to sign a contract confirming that their wares have been “obtained in a legal way”. In response to the allegations made by Polish prosecutors about the stolen books, Burmistrov said, “We do not sell books from state libraries with any stamps that our experts may define as state-library stamps.”

By looking at the prices fetched by similar books at Russian auctions, the University of Warsaw library estimates that the total value of its missing volumes could be nearly $1m. But, as Jandy put it, “Those books were not for sale. They were part of our cultural heritage. So they didn’t have a market value.”

When I asked other Poles about this notion that their “cultural heritage” had been stolen, they reacted with ambivalence. The University of Warsaw houses the largest collection of 19th-century Russian books outside Russia—an important reminder of a bitter century in Poland’s history, when it was subjugated by the Russian Empire (save for a brief interlude between the world wars, Poland wouldn’t become an independent nation again until 1989). To lose the books, a former university librarian told me, felt like an obfuscation of that history; to be robbed by the country’s old imperial overlord also felt like sublimated aggression, particularly since Poland’s influence in Europe is growing as it provides military and financial support to Ukraine. Jandy’s assistant, a young man named Jacek Szkudlarek, said that the fact that these books “were stolen back to Mother Russia…it stinks”.

The thefts of Pushkins and other rare books have abated, perhaps because so many members of the Tsirekidze gang have been arrested. In June, Mikheil Zamtaradze was convicted in Lithuania for stealing the 17 books from the Vilnius University Library. In court, he shared several intriguing tidbits: he claimed that he had been paid $30,000 in cryptocurrency by a man in Russia to seek specific titles—and that the Russian buyer had sent him 12 of the forgeries used in the thefts.

Most of the stolen books have still not been recovered; many probably never will be, as Russian law makes it hard to remove items of cultural value from Russia. “The only possibility now for those books to be returned is if a collector buys them, understands where they came from, emigrates to, I don’t know, Poland, and gives them back,” Achechova, the librarian in Paris, said. “It is legally impossible to remove works more than 100 years old from Russia, and these laws have only hardened in recent years.”

Georgian prosecutors have persisted in their investigation, making another round of arrests in December. But as I sat with them in their brutalist office building in Tbilisi, I sensed that they were as ambivalent about the thefts as their Polish peers. People seemed discomfited by the historical wounds that these crimes re-opened, yet also harboured a grudging regard for the thieves’ ingenuity. Our conversation periodically devolved into chuckles as the prosecutors recounted their initial reactions to the thefts. “We all found it so weird,” Meri Kajaia, who works in the international-relations division of the office, told me. “I mean, yeah okay, theft of jewellery, theft of money, theft of everything. But theft of books?” She had never heard of most of the titles that were taken.

Tkeshelashvili, the head prosecutor, didn’t much like Pushkin himself, having been forced to memorise his poems as a child when Georgia was under Soviet rule. “We don’t really care about the books,” he admitted with a wry smile. “Just the crime.”

The articles may contain material provided by third parties derived from sources believed to be accurate at its issue date. While such material is published with necessary permission, the Westpac Group accepts no responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of, nor does it endorse any such third-party material. To the maximum extent permitted by law, we intend by this notice to exclude liability for third-party material. Further, the information provided does not take into account your personal objectives, financial situation or needs and so you should consider its appropriateness, having regard to your personal objectives, financial situation and needs before acting on it.