The earthling’s guide to building a Moon base

This article has been kindly reproduced with permission from The Economist and was published on 6 December 2024.

Charlie Duke arrived on the Moon, in 1972, after what felt like an eternity. First, the launch from Earth had been delayed by a month because of last-minute technical problems. Then, four days into the voyage, he had clambered into the lunar landing module with his fellow astronaut, John Young, only for mission control to tell them to stand by – the spacecraft that was to stay in orbit as they went down to the Moon had a problem with its engine. Six hours passed before they were given the green light.

Finally, Duke and Young began their descent towards the Moon in a landing module that was roughly the size of a lift. On its walls were buttons and levers, and tiny portholes for the astronauts to peer through. Since there were no seats, they stood side-by-side, stuck to the floor with waist tethers and Velcro on the soles of their boots. Once they touched down, mission control ordered the astronauts to rest before their first excursion. It was the last thing Duke felt like doing.

After powering down the module, the astronauts unrolled two hammocks and strung them up so they criss-crossed the cabin. “My mind was racing,” Duke told me. “We put some shades up over the windows to keep out the sunlight, and we dimmed the lights in the cockpit. But it was just the excitement of being on the Moon. Finally, I had to take a sleeping pill.”

When mission control decided Duke and Young had rested long enough, they let them out to explore. The astronauts unshipped their buggy and steered it around the undulating landscape near the Descartes crater, which is 48km wide and nearly a kilometre deep. Hopping about in their spacesuits – the Moon has a sixth of the Earth’s gravity – they collected samples of dust and rocks before returning to the lander.

Duke and Young ate two meals a day, adding cold water to pouches of dehydrated food which claimed to contain things like beef stew, fruit cake and grape punch. The astronauts urinated and defecated into bags that were prone to leaking. They had to knead antiseptic into them to prevent a build-up of gas. Despite the privations, Duke found the experience thrilling. “We were living on the Moon for three days. And it was a sense of wonder. I never got over that.”

Duke and Young were among the last to walk on the Moon. In 1975 NASA ended the Apollo programme and no one else has set foot on the Moon since. But that could be about to change. Half a century on from that mission, the Artemis programme, run by NASA in collaboration with the Japanese, Israeli, German, Italian, Emirati and European space agencies, is trying to put astronauts back on the Moon.

These new missions will last longer than they did in the 1960s and 1970s, with astronauts staying on the Moon for weeks, possibly months, at a time. The space agencies involved in the Artemis programme are racing to design permanent lunar bases. The Chinese and Russian space agencies are also collaborating on their own Moon base.

Examples of otherworldly habitats already exist. The International Space Station (ISS) has been orbiting for two and half decades and China’s Tiangong space station has been permanently crewed since 2022; they were preceded by Russia’s Mir space station and America’s short-lived Skylab in the 1970s. But these vessels orbit just a few hundred kilometres above Earth – practically commuting distance compared with the 384,400km you have to travel to get to the Moon.

Moon bases will also have to protect astronauts. The Moon is especially vulnerable to meteorites: millions of years of collisions have left its surface pockmarked and covered with dust, as fine as powdered sugar. Incoming rocks could puncture the walls of a Moon base, allowing life-supporting atmospheric gases to escape into the vacuum of space.

Astronauts are also vulnerable to the radiation produced by cosmic explosions and solar flares. Radiation can increase the risk of genetic mutations that can cause cancer or neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s.

On the ISS a type of plastic called polyethylene is used to protect astronauts from these rays. (Polyethylene is rich in hydrogen, which acts as a shield against radiation.) Even with such protection, astronauts can suffer genetic damage if they spend more than a few months in orbit.

Lunar architects reckon that storing water in the walls of a Moon base could ward off radiation. The water could also be used for drinking, bathing or even as fuel for hydrogen-powered Moon buggies. Finding and gathering water on the Moon, though, is no simple task. Water there has a habit of disappearing as soon as the Sun’s rays touch it, turning from ice into vapour. The best bet for discovering a reliable water source is in one of the regions that is shrouded in perpetual shadow – a deep crater near one of the poles, where satellite data has suggested there might be ice. (All current plans for Moon bases are in the vicinity of its South Pole.)

As well as fortifying itself against external threats, a Moon base will also have to minimise dangers within. To support human life, it will have to contain a mixture of gases, mostly nitrogen and oxygen. The risk, given the Moon’s lack of atmosphere, and therefore lack of countervailing pressure, is that these gases could cause a structure to burst at its seams. This is why many Moon base designs feature ovoid shapes and squat domes: spheres distribute pressure more evenly than a cube.

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and the European Space Agency (ESA) recently asked lunar designers to imagine what a Moon settlement could look like. Colin Koop and Daniel Inocente, who work for SOM, an American architecture firm, suggested squat towers with a footprint shaped like a three-leaf clover. “You don’t fully appreciate what Earth gives you as a human being until you try to design something outside of Earth’s atmosphere,” Koop told me. “As a designer you realise the architecture has to provide all these things that Earth would provide otherwise.”

Then, of course, there’s the problem of how to actually build a Moon base. Even though private rocket companies such as SpaceX have brought down the cost of launching tonnes of metal and fabric into space, transporting supplies to the Moon remains wildly expensive: it costs around $220,000 per kilo to bring building material to the Moon. One solution is to use stuff that’s already there – which, on the surface of a rock that is constantly pelted with flying debris, is a lot of dust.

Last summer I visited a hangar in Austin, Texas, to meet some people who are working out how to construct buildings with Moon dust, or to be precise, regolith: a combination of dust and broken rocks. Under the microscope, regolith, which is also found on the surface of the Earth, has sharp angles. “You can think of it like those weeds with sticky burrs,” Georgiana Kramer, a geologist at the Planetary Science Institute, told me. “The shape of one grain of regolith is so rugged and jagged and all the breaks on it are very angular.” It can penetrate a space suit or an electronic device, and can cause lung damage if inhaled. (Duke and Young had to vacuum a thick coating of regolith from their space suits before they got back in their spacecraft.)

In 2022 NASA awarded a $57m contract to ICON, a construction firm that uses robotic 3D printers to make large-scale housing developments, to adapt their technology for building a Moon base “in situ”. (China intends to experiment with in-situ construction methods on its uncrewed Chang’e-8 mission to the Moon, which is scheduled for 2028.)

Evan Jensen, an executive at ICON, showed me a one-armed robot builder the company is developing. The machine, a set of shining, metal spars that can pivot on multiple joints and spin around its steel base, was taller than me; its arm stretched out mid-grasp like an idle crane. Eventually, explained Jensen, the robot will be able to scoop up Moon dust, compact it and sinter it in place with a laser. “Like Cyclops from the X-Men,” said Jensen.

When I visited, the team was trying to get the robotic arm to work in concert with a sintering device. On the floor of a shipping container was a shallow box filled with fine grey sand: crushed feldspar rocks from a quarry in Montana. Their geological make-up makes them a reasonable substitute for regolith. A miniature version of the one-armed robot, about the size of a Hoover, hovered above. On the other end of the container was a laser encased in a vacuum tube to simulate lunar building conditions. (ICON has made progress since my trip: visitors to the hangar can now watch a robotic arm with an integrated laser attempt to build in a specially constructed vacuum chamber.)

Jason Ballard – ICON’s co-founder and chief executive, an energetic, cowboy-hat-wearing space enthusiast – handed me something the laser had made earlier. It was a heavy, cylindrical stone with a grainy surface and glassy crevices, like obsidian. Researchers have dubbed it “the Dr Pepper can”. Ballard was pleased with the “accurate shape” the prototype had created. “Like, number one, can you make a robot do this? Number two, will it give you building materials that will survive the conditions of the lunar surface, and then, to make it even harder, can you do it in a vacuum? And so far, we’ve sort of passed with flying colours. It makes us all feel like this isn’t science fiction.”

There are other problems that ICON engineers need to resolve. Much of the geological material on the Moon is dark, iron-rich basalt or light, hard feldspar, but its chemical profile changes depending on where it’s found. So far the team has experimented only with one kind of material – a synthetic regolith that is low in basalt. They plan to try out different materials, and to programme the robot to analyse the chemical make-up of the dust and manipulate the laser accordingly.

ICON’s engineers have already realised that by adjusting the intensity of the laser, they can transform Moon dust into matter that is closer to glass or ceramic than stone. Being able to turn dust into different types of building material will enable them to build all sorts of lunar infrastructure.

“One of the first things you would need is rocket landing and launch pads so that you don’t destroy the Moon base you’re trying to build every time you land and take off,” Ballard told me. Landing directly on the surface of the Moon “sends all the dust and rock out at ballistic trajectories…like a machinegun every time,” he said.

The next step would be building roads that connect landing sites to temporary shelters. After that, the focus would shift to harnessing solar energy, collecting and storing water, producing food and oxygen, and processing waste.

But anyone hoping for five-star accommodation will be waiting a long time, Ballard warned. “You’re expecting people who have a pretty high tolerance for roughing it, because it’s not going to be the Ritz, it’s not going to be the Four Seasons for a while. It’s going to be a difficult, challenging place. But none of those things take a miracle to happen.”

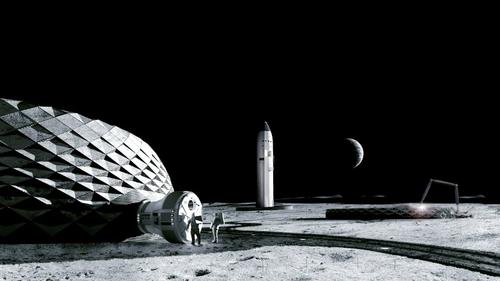

On a table in the middle of the space hangar was a model of the Moon base that ICON hopes eventually to build. It was designed by Bjarke Ingels, a Danish architect whose portfolio ranges from New York skyscrapers to an eco-friendly power plant in Copenhagen. On the Moon base are three habitats that look like giant pineapples with the top sliced off – a shape that a one-armed robot can easily build by using a circular motion. Triangular “buckets” in a harlequin pattern jut out from the exterior walls. Loose lunar dust could be poured into them to provide insulation and protect inhabitants from radiation.

Inside the habitats, curved walls create vaulted ceilings. Their height – roughly five metres – was chosen so astronauts would have enough room to bounce around (the average Moon jump is 3.6 metres high). Even at miniature scale, the buildings looked stately. “It has this almost temple-like geometry,” said Ingels.

NASA has produced a handbook for space architects and designers to consult, with advice on things like the best surfaces to use to prevent microbial growth. It also describes what Moon dwellers might like to do in their spare time. In the past, astronauts have enjoyed looking at Earth and listening to music, along with zero-gravity acrobatics.

Koop, in his design for the MIT and ESA project, had thought a lot about leisure time. Many previous designs for space habitats looked like pilot cockpits, with every inch covered with instruments and panels. That might work for short missions, but not for extended stays. Imagining a bored astronaut bouncing a tennis ball repeatedly against a wall, Koop decided to include spaces that were relatively empty, where function and use wasn’t strictly prescribed.

It’s important to allow for spontaneity, said Koop. “People don’t realise that every minute of an astronaut’s life is planned out months and years in advance as part of the mission, and the expectation for human performance in space is to stick to that script and never, ever break from it,” Koop told me. “At what point are you off the clock? At what point are you unpredictably human and not adhering to any script other than what you feel like doing?”

Today’s space designers might look to their predecessors for inspiration. Galina Balashova, an architect who worked for the Soviet space programme, said space stations should have contrasting dark green floors and pale yellow ceilings, to help astronauts feel grounded as they revolve in the absence of gravity (she also recommended hanging watercolour landscapes on the walls). A module at the ISS retains the colour scheme, although it’s difficult to make out because the interior is so crowded with cables and technical equipment.

The shape of a future lunar base will depend on what humans decide to do on the Moon. Will they be working or playing? Many of the designers I spoke to said the Moon base would have to fulfil a similar function to McMurdo station in the Antarctic – a desolate research lab. But they also acknowledged the Moon’s tourism potential. “It’s where people go when you want to find thrills and you want the most dangerous experience,” Inocente told me.

If the Moon became a viable destination for tourists, the money they spend could fund further lunar exploration. Might people one day build cities on the Moon? Robert Howard, an engineer at NASA, said this depended in part on whether there was enough demand for space travel to make the project commercially viable. “It’s not just the engineering of how we build these structures, but it’s also the economy, the political science, the sociology of how does humanity transform from an earthbound culture to a culture that actually wants to go to another Moon or another planet?”

The articles may contain material provided by third parties derived from sources believed to be accurate at its issue date. While such material is published with necessary permission, the Westpac Group accepts no responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of, nor does it endorse any such third-party material. To the maximum extent permitted by law, we intend by this notice to exclude liability for third-party material. Further, the information provided does not take into account your personal objectives, financial situation or needs and so you should consider its appropriateness, having regard to your personal objectives, financial situation and needs before acting on it.