Ashes to showers, dust to crops

Gillian Sanbrook’s NSW property Bibbaringa is still green and growing while the drought rolls on. (Supplied)

On August 8, 2018, when it was declared that 100 per cent of New South Wales was in drought, Gillian Sanbrook posted a social media video: a trail of 320-plus-kilogram steers, moving slowly into a fresh paddock to nibble contentedly on long green grass.

The video sparked immediate interest in how Sanbrook’s property was thriving at a time Australia was heading into its driest month on record, second only to April 1902 according to the Bureau of Meteorology.

“I’ve had less than half the average rainfall this year – which is more than a lot of people – but my property is still green and growing,” Sanbrook wrote.

While the wait continues for the big dry to break in drought-stricken regions, interest in her “holistic land management” approach remains keen. Weather and ocean patterns indicate the drought is likely to be locked in until at least autumn 2019 according to the Bureau’s climate models, and its El Niño “watch” was upgraded to “alert” in October – an unwelcome sign for the agriculture sector, as El Niño events typically produce drier-than-normal conditions in eastern Australia.

Sanbrook says her 1000-acre property, “Bibbaringa”, located in the southern slopes of NSW, wasn’t always in such good shape. When she bought it in 2007 during the Millennium drought, it was overgrazed and overrun with rabbits and Paterson’s Curse. The soil, creeks and gullies were eroded. Whenever there was a downpour, water poured off the slopes. And it was overstocked, with 600 cows, 2000 sheep and 90 horses.

The drought in NSW is not expected to break before autumn 2019, according to Bureau of Meteorology climate modelling.

The first thing she did was de-stock and rest the property for six months, making ground cover her top priority.

“If you’ve got ground cover, you’ve got photosynthesis happening, utilising the energy from the sun and producing good root structure,” she says, adding that good roots keep the rain where it falls.

She says she did not renovate the pasture. “I figured the plants would appear that needed to appear.” And after just one year, the Paterson’s Curse and capeweed disappeared and Bibbaringa’s ground cover increased.

“And once the rain started to come, we only had a small number of stock and moved them around in a holistic management planned rotational graze,” Sanbrook says. “I will sell stock if I think the ground cover is going to be threatened,” she says.

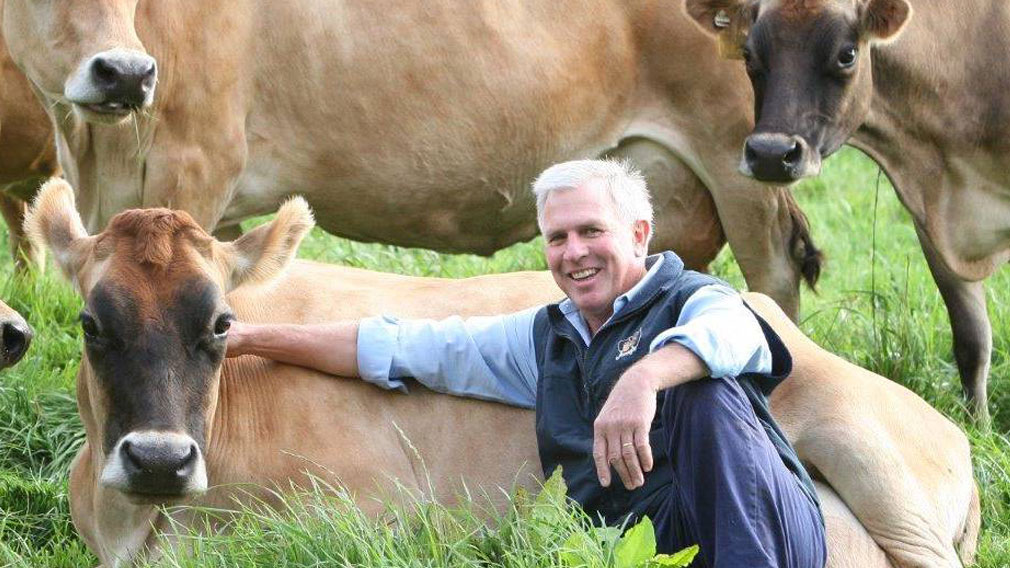

NSW Northern Tablelands organic beef farmer Glenn Morris says his property "Billabong" was also significantly degraded when he started work on it.

“It took about five to eight years to really get that soil health back and holding water,” says Morris, who twice saddled up his horse, and rode across the Sydney Harbour Bridge leading the Time2Choose rally to raise awareness of environmental issues affecting farmers.

NSW organic beef farmer Glenn Morris, who twice led a rally to raise awareness of environmental issues affecting farmers.

Morris and his family help run two properties for FigTrees Organic Farms, practising “biological farming” and regenerative agriculture, with a focus on soil health.

Through the dry months of 2018, Billabong has maintained 100 per cent ground cover and, like Sanbrook, Morris makes this a priority. “The main thing is we don’t take pastures too short,” Morris says. “We make sure to keep a residual of grass there so you’ve got some roots holding the soil together.”

Morris believes ground cover can be achieved even in severely dry areas. “We’re in a terrible drought, but you look at the side of the road even in those really bad areas, and there’s still ground cover,” he says. “It’s dry but it’s still there.”

Another principle followed by Sanbrook is to keep a strict grazing schedule and she buys stock according to rainfall predictions.

“I know in the next 90 and sometimes out to 240 days where the cattle are going to be. And if I start to move faster than I should be, I can very quickly see that things are not going as well as I thought they would, and I have to de-stock early and sell them directly to the grass-fed, no-hormone and no-antibiotic market,” she says.

Sanbrook doesn’t worry about rebuilding stock in the future as she knows she can buy the same or better quality again. “The genetics in Australian livestock is just so good.”

Shannon Kelly, who runs pasture-based, regenerative Full Circle Farm in Dooralong Valley, shares a similar vision, to produce food without destroying nature.

“Not just sustaining it but regenerating it, leaving it in a better state for our children”.

For a start, Kelly doesn’t make hay. “From spring to autumn, we’re struggling to have enough animals on the property – but then we have a dormant period of around 120 days over winter where grass is shut down,” he explains. “So, coming out of autumn, we stockpile our grasses and instead of harvesting it, we leave it in our paddocks to dry. Then we ration it out to the animals using electric fencing.

“We sell our beef to a customer base locally on the coast – we start processing in January, almost halving our herd size going into the dormant period. Then, come spring, we stock up with weaners.”

Kelly says his animals are a vital tool in building drought and flood resiliency into Full Circle Farm: “If the ground is covered by mulch from cattle hooves or a thick sward of pasture, it takes longer to dry out, keeps the soil surface cooler and encourages earthworms. Our cattle are moved daily, mowing down and fertilising the grass. Our chickens follow behind, scratching through the manure, eating creepy-crawlies and adding their own fertiliser.”

Another important principle is to manage “the city under the ground”, according to Morris. “And unfortunately, synthetic fertiliser and chemicals are absolutely annihilating our soil biology,” he says.

Holistic land management includes managing "the city under the ground".

Home to diverse organisms, from bacteria to fungi, algae, worms, ants and even small animals, the “city underground” thrives on humus, the dark-brown organic fertiliser from biodegraded dung and dead stuff that’s so rich in carbon and nutrients.

Morris notes that humus also improves the water-retaining properties of soil. “If we add an extra 10 per cent of humus into the soil over one hectare at 30 centimetres of depth, we [can] store an extra 1.6 million litres [of water] per hectare – we start getting rivers flowing; we start creating abundance again.” And miraculously, “by holding the water, when it does rain, in that sponge that is healthy soil, you actually get more rain, because the vegetation pumps it back up and creates more rain”.

The simplest way to build humus is to start enhancing perennial grasses and trees, but it takes time.

Sanbrook’s Bibbaringa now has more than 60,000 native trees, most planted a decade ago using government grant funding. “We planted eucalyptus, wattles, hakea, she-oak, shrubs, trees and grasses in fenced tree-lots up to 16 hectares in size,” she says.

Sanbrook considers factors such as the organic-carbon percentage and the water-holding capacity of the soil as other tools with which to create income.

“A lot of people think, I’ve got to make money first, and then the rest will just fall into place. Well, I think it’s the other way around,” she says.

When Bibbaringa’s dams and creeks were filled to capacity, Sanbrook added contours, slowing the flow of water through the landscape. Now water was being stored underground, in dams, and along the contours.

She says, “It doesn’t happen as quickly as going out there with tractors and sowing seed into the property using artificial chemicals and fertiliser. But you get the results.”

Morris says a recent study was conducted by the ANU Fenner School of Environment & Society into farm profitability and biodiversity, comparing data from regenerative farmers and traditional farmers.

“We stacked up as good or better as conventional farmers in terms of financial outcomes, and in terms of ecological and personal, general health, we were way out in front.”

But farmers need support to take such long-term strategies on board.

Fiona Simson, President of the National Farmers’ Federation and a farmer from the Liverpool Plains, says stability and continuity of leaders is needed.

“Farmers deserve nothing less. Our cotton and grain industries lead the world in water-use efficiency. Farmers have significantly reduced their reliance on fertilisers and chemicals. To keep agriculture growing to become a $100 billion industry by 2030, we need to build resilience and these modern skill sets into every farm business.

“We need to remove much of the red tape applied to land management,” Simson says. “There are market-based options that will deliver better outcomes for biodiversity by valuing public good conservation on private land and rewarding farmers for protecting threatened species.”

This is an edited version of an article that first appeared in the Summer edition of Produce Magazine, by Westpac Agribusiness. Additional reporting by Paul Robinson.