How a 10-year-old tragedy turned transformative for young farmers

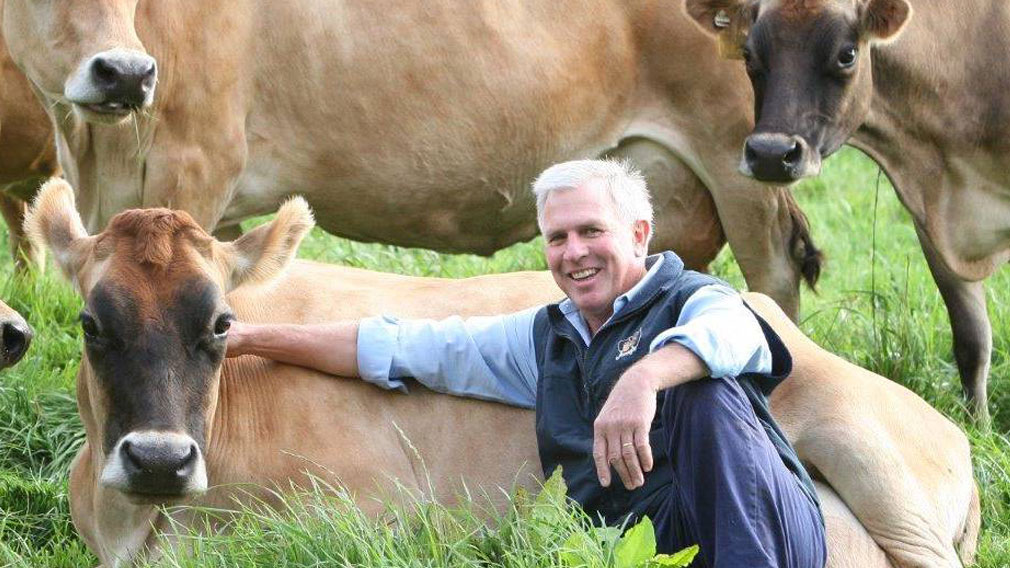

Australian cattle industry champion, the late Zanda McDonald. (Julie McDonald)

Ten years ago, shock ripped through the Australasian cattle industry following the tragic death of influential beef farmer, Zanda McDonald, after a farming accident. He was aged just 41.

For those closest to him, the years haven’t erased the profound sense of loss of the well-respected cattleman, husband and father.

But just as Zanda helped shape his industry in life, his influence has endured through a leadership program – the Zanda McDonald Award – set up in his honour in 2014, which has turbocharged the careers of dozens of young progressive agriculturalists.

“It would be something I know, had he still been with us, he'd be incredibly pleased to see,” says friend and industry leader Shane McManaway, who founded the award, now one of the most prestigious in the industry, and set to announce its ninth annual winners March 15.

“It’s what he believed in – it’s lifted a lot of young people's aspirations to have a crack, and that can only be good for agriculture across Australasia.”

Zanda – short for ‘Alexander’ which, as family legend goes, stuck since the teacher of his first school class, via radio with School of the Air, needed to tell him apart from another little boy with the same name – had cattle farming in his genes.

Growing up at his family’s remote property, Devoncourt, around 70kms from Cloncurry in Queensland’s north-west, he was among seven generations of McDonalds to farm cattle in Australia since 1827. MDH Pty Ltd, the family’s business, has grown to be one of Australia’s largest beef cattle operations, with a herd of around 150,000 on 14 properties across Queensland.

Running the operation alongside parents Don and Christine, uncle Bob and aunt Susan, cousins and siblings and their spouses, Zanda is credited for transforming MDH from a cattle raising business to a fully integrated beef supply chain, at one point exporting to over 20 countries.

“He was a visionary,” reflects Julie McDonald, Zanda’s wife.

“He'd be embarrassed by that word, but he was. He was just a big thinker, like the rest of his family is – always looking to where problems may lie ahead and what we could do to make our business – and therefore the industry – better.”

Julie McDonald (centre) with daughters (left to right) Katie, Bella, Laura and Millie. (Supplied)

One of the industry issues he’s best known for leading was the introduction of pain relief for young cattle undergoing common procedures such as castration, dehorning and branding.

In the early 2000s, Zanda had been alert to the pressure building on sheep graziers to minimise pain during the controversial practice of mulesing, where strips of skin are removed from around a sheep’s breech to prevent the deadly parasitic infection flystrike. Although similar activism hadn’t zeroed in on the cattle industry, Zanda predicted it would.

“That was his sense, and he was so right,” says Julie, speaking from the homestead at Devoncourt where she lives and works with the family as MDH’s chief financial officer.

“The way he saw it, bringing in pain relief was going to be good for our business because we'll have this ethically produced beef, but most importantly it’s going to have a huge implication for animal welfare.”

Rising to the challenge, Zanda teamed up with Australian Wool Growers Association director Charles “Chick” Olsson, who’d been leading a group that pioneered a pain management product for sheep, to become known as Tri Solfen. Together with a handful of other backers they worked on a product suitable for cattle which was trialled extensively on the McDonald’s cattle.

Zanda was keen for pain relief to be adopted across the industry, and in 2012, began publicly advocating the practice along with the development of an off-the-shelf product that producers could pick up locally.

His views were not met with open arms by the entire industry, some pockets of graziers concerned about the impost of its cost and time. But Zanda was determined to manage his own herd’s pain, and over time all major pastoral companies followed suit, the practice now written into cattle welfare standards.

His innovative spirit saw him involved in a number of other pioneering research projects, such as cutting-edge stem cell research, trials at abattoirs with respect to eating quality, and trials with CSIRO to develop a genomic estimated breeding value for daughter fertility in herd bulls.

“Zan had a world view and an inquiring mind, and he’d always team up with others to work for an outcome that could benefit the whole industry,” Julie says.

Shane McManaway, founder and patron of the Zanda McDonald Award. (Supplied)

McManaway recalls the immediate affinity he felt with Zanda when they met at a cattle industry event in the early 2000s.

“Even though he was younger than me, he had a very old head on young shoulders,” he says, speaking from his mixed farming operation in the Wairarapa region of New Zealand, his focus since retiring after almost two decades as CEO of international animal identification company AllFlex.

The more he and Zanda put their heads together over the years to share ideas, the more they felt the industry needed a platform to bring other likeminded pastoralists together to “have a yarn” about tackling some of the industry’s biggest issues. This was realised in 2005 when McManaway formed the Platinum Primary Producers, a forum which grew to a collective of 150 of Australasia’s leading farmers, to build what he calls “the first agricultural bridge across the Tasman” during almost 15 years of operation.

McManaway recalls how tough it was for all PPP members when they learned of the shocking news about their “dear friend”. Zanda had been out on the family property working on a routine repair of a windmill, about 4 meters from the ground, when he fell, sustaining head, spinal and chest injuries.

“For months after that I was contemplating Zan’s death, feeling for Julie and their kids, and feeling sad about the whole damn thing,” he says.

“Nobody's had the same degree of effect on me as he has. He portrayed all the values of what it is that holds the primary production sector in such good stead. He would speak up and talk with conviction about what he believed in but in a way that made people listen.

“He had a profound effect on everyone who knew him."

The Zanda McDonald Award honour role. (Supplied)

As he reflected, McManaway recalled one of his friend’s biggest industry concerns – the need to attract and support good young people in agriculture – prompting him to sketch out the bones of the award he felt would tackle it, all in Zanda’s name.

After obtaining the blessing of Julie and the rest of the McDonald family, McManaway called on all members of the PPP group to support the newly formed award by becoming mentors for its finalists and winners.

“Effectively we got the key to the door of 150 of Australasia's best famers, so that young people entering could always go and seek their guidance and counsel,” McManaway says.

“It’s been life changing for finalists and winners; their careers have been catapulted, largely because they've got so many mentors around them prepared to support and give them guidance,” he says.

Emma Black, the very first award winner, in 2015, agrees.

“There’s no doubt that Blackbox would not exist if it weren’t for the award,” says the Queensland based agriculturalist of the agritech business she co-founded in 2019 with fellow Queenslander Shannon Speight

Black, who grew up on a sheep station 140km west of Longreach, was 27 at the time of her nomination and had been working with northern beef producers for a decade, predominantly via her role with Queensland’s Department of Agriculture and Fisheries. She met Speight, who also worked in the northern beef industry, when she too was nominated for the Zanda McDonald Award in 2019.

“We ran ideas past each other, started doing a few projects together, and became good friends,” recalls Black, who now calls Kingaroy, around 200km north-west of Brisbane, home.

Julie McDonald (centre) with Shannon Speight (left) and Emma Black (right), both Zanda McDonald Award winners and cofounders of agritech business, Blackbox. (Supplied)

At the time, Speight, a qualified veterinarian based in Ravenshoe in the Atherton tablelands, had been coordinating a large-scale genomics project with the University of Queensland.

As they were handling a lot of data through their work, they’d noticed the siloed way data was collected along the cattle production supply chain. Realising this was an issue for farmers, as they were unable to get the full picture needed to improve their sustainability and efficiency, the pair sketched out a solution.

Speight was able to bounce their idea off numerous cattle industry leaders during a mentoring trip organised as part of her Zanda McDonald Award win. A number of them, including McManaway, quickly recognised the calibre of the pair’s capability, to the point they tipped their own money into their fledgling business.

“We knew we were onto something,” says Black, whose list of accolades continues to grow, including being nominated earlier this month as a state finalist for Agrifuture’s Rural Women’s Award.

“We knew we'd have financial support; and we knew producers wanted it – and we knew all that purely because we had access to that incredible network of experienced producers who were quite happy to take a phone-call from a couple of young sheilas with a random idea and talk it through.”

Both Black and Speight left their jobs in 2020 to throw themselves full time into developing Blackbox, which has since grown to a staff of 12.

The startup has gained huge traction in all segments of the supply chain, attracting customers from all over the country. It now tracks around 3 million cattle and 36 million data points – including “crush side” statistics like each animal’s weight, pregnancy status, breed and date of birth; along with feedlot performance and carcass data – enabling producers to interpret and act on trends and lost opportunities identified in the data.

Richard Rains, chairman of the Zanda McDonald Award. (Supplied)

The long-time chairman of the Zanda McDonald Award, Richard Rains, says Black and Speight exemplify the ethos of the award, which has so far chosen 11 winners from dozens of finalists in Australia and New Zealand.

Well known in the industry as one of Australia’s most successful beef exporters having headed up meat export company Sanger Australia for decades, Rains knew Zanda well, forming a friendship when the young farmer was keen to learn more about what happens beyond the farmgate as he was forging a ground-breaking path for MDH towards exporting.

“I often ask award recipients to reflect on what they think they might have to do in their lives to have the honour of an award in their name by the age of 41,” Rains says.

“It's quite an extraordinary feat to have made such an impact in a large industry at such a young age, and there is absolutely no doubt that he was well worthy of it because he was an extraordinary man.”

For Julie, she’s unquestionably proud of the role the award is playing in developing the leadership skills of the upcoming generation.

But, more so, she wishes Zanda were here to see it.

Westpac is a sponsor of the Zanda McDonald Award.