Burps, beams and batteries on low carbon milk path

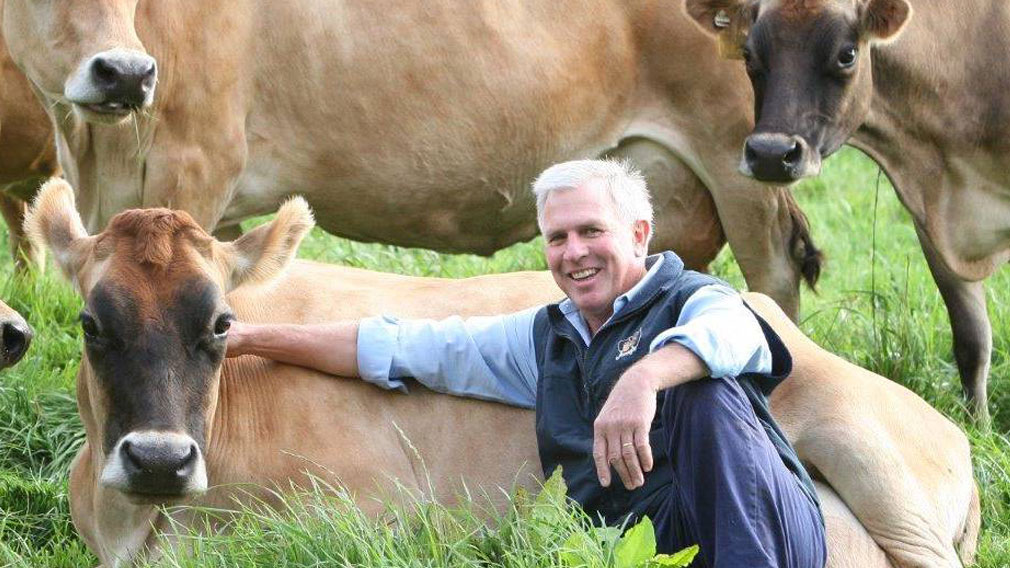

Dairy farmer John Pekin is about to trial a new of way of reducing his herd’s methane emissions. (Suppliers)

Big changes underway by John Pekin to lower his dairy operation’s emissions are viewed by the fourth-generation farmer as a business imperative as much as an environmental necessity.

“I’m very commercially minded,” says the owner of a 950-cow dairy farm near Simpson in regional Victoria, around 200 kilometres south-west of Melbourne.

“And I very much believe that those of us who do something now are going to be in a far better space in the next decade, than those who don't.”

The changes revolve around lowering his 450-hectare farm’s carbon emissions – a challenge common to most industry operators, but with unique complexities for a farm with big numbers of ruminant livestock.

Pekin is set to embark on the next phase of a plan kicked off three years ago that he hopes will get him closer to neutralising his farm’s emissions within 18 months, a move he sees as good for the environment and his back pocket.

In the past year, he’s put solar panels on his sheds which generate up to 270-kilowatts an hour of electricity, hooked up to 520-kilowatt hour energy storage batteries. This means the commercial dairy – which he’s run with his family since finishing school the early 1990s until taking the helm from this year with wife Rochelle – is powered almost entirely by renewables.

His attention now is turning to his herd’s methane emissions.

“Our approach is going to be to measure everything every day,” says CommPower Industrial’s Nick d’Avoine, who is managing a trial which aims to reduce emissions from Pekin’s stock.

Pekin aims to reduce his 950-cow herd’s methane emissions. (Supplied)

“We're putting a methane meter in every single milking bail to measure how much methane actually comes out of each cow,” says d’Avoine, referring to the little puffs of gas that waft into the atmosphere every time a cow burps or passes wind.

“We’ll do that over a couple of months to measure the baseline; we’ll then implement a feed change and measure the results.”

The trial is one of several across the globe as the dairy industry hastens to find a sustainable, commercially viable way to reduce the enteric methane that naturally occurs in the stomachs of ruminant grazers, including the world’s 1 billion cows, as they break down the plants they eat.

Their every exhalation produces a short-lived but potent greenhouse gas, the second-largest contributor to climate change after carbon dioxide. Livestock emissions account for around 10 per cent of Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions, according to the Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources.

It’s caused countries around the world to consider solutions, including a recent idea flagged by the New Zealand government to introduce a so-called “burp tax” on cattle and sheep farmers. Speculation has also gathered pace this week that Australia’s new federal government could sign up to the Global Methane Pledge, committing to limit global methane emissions by 30 per cent from 2020 levels by the end of the decade.

John Pekin (left) and CommPower Industrial’s Nick d’Avoine. (Supplied)

D’Avoine, whose Melbourne-based firm also customises energy efficiency plans for commercial clients, says the pool of evidence is growing that certain products when added to a cow’s diet can reduce their methane emissions by up to 95 per cent.

“Feeding these products to the animals, it gets in the stomach, reacts with the methanagens inside and kills them before they can turn into gas and get burped out,” he says.

“It’s still very much in the test and see phase, but we believe being able to do something on a full-scale commercial basis in a dairy is about 6 to 12 months away.”

The cows’ feed at Pekin’s dairy will be supplemented with a product extracted from molasses from Queensland sugar cane, which d’Avoine says has shown promising results in early small-scale studies, reducing a cow’s methane production by up to 80 per cent.

Among other feed additives sparking interest globally is a species of red seaweed native to Australian coastal waters called Asparagopsis. FutureFeed, a research company born out of CSIRO, said last year feedlot trials in beef cattle using less than 1 per cent of Asparagopsis reduced methane by more than 95 per cent.

Non-food-based methods are also being investigated, such as a harness developed by ZELP (Zero Emissions Livestock Project). It’s worn around the head of the cow and captures and oxidises gas as the animal exhales.

“We want look at all of the different types of products to see which one works best for John while ensuring that the milk processors are happy for that additive to be put into the mix for the milk they then receive,” says d’Avoine, who reckons hundreds of dairy farmers await the trial’s outcome in anticipation of implementing similar initiatives in their own operations.

Energy storage batteries enable Pekin’s dairy to be powered almost entirely by renewables. (Supplied)

Rhonda Henry, a relationship manager at Westpac who has known the Pekins for around 30 of her 50 years in agri banking, says John Pekin is among a growing number of farmers who are on the "front foot" in trying to mitigate sustainability risks.

“Most of the farmers in the region view themselves as custodians of the land, and they’re aware that expectations are changing,” she says, noting the headwinds faced by the industry which have seen dairy numbers shrinking from a national peak of more than 22,000 in the 1980s to 4618 at the end of last year.

“That’s driving them to make their farms as clean and green as possible for the future generations.”

Solar panels on Pekin’s sheds generate up to 270-kilowatts an hour of electricity. (Nick d'Avoine)

Pending positive trial results, and when combined with his renewable energy conversions, Pekin says his farm’s carbon neutrality could put him in a position to consider selling carbon credits, and negotiating better milk prices with processors who reward low carbon producers. It’s also slashed his power bills, which had more than doubled from around $30,000 to $70,000 in the space of five years, before solar was installed.

“I'm still making my money out of milk now, but I can actually see that I can generate more income by going down this path. It all seems to be starting to crystallise.”

Although conceding he couldn’t have afforded the initiatives if he’d not won financial grants from the Victorian government, Pekin says the prices of technology – like renewable energy storage batteries – will continue to drop, and the investment in keeping dairy in a “sustainable space” makes good business sense.

“We're in an industry that probably hasn't done enough, so it’s the thing that this generation can work on,” he says.