Young science fan turned ‘EduTuber’

Science communicator Toby Hendy says social media can be a powerful way to spark young people’s interest in science.

Most teenagers are more likely to be watching gamers or music videos on YouTube in their spare time than experimenting with science.

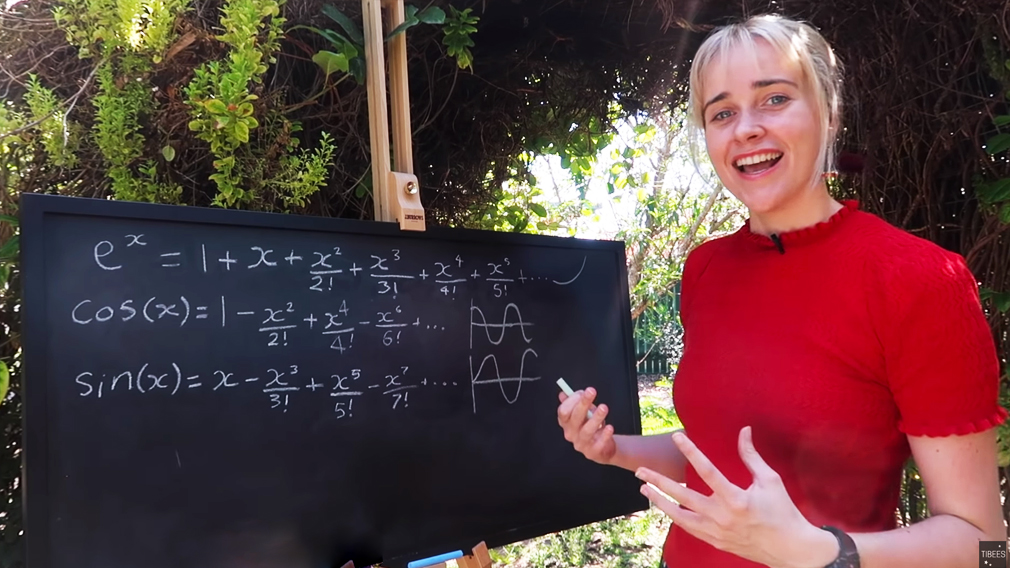

But for Toby Hendy, a love for physics sparked by watching scientific channels on YouTube and television led her to produce her first physics video – about time travel – on her own YouTube channel Tibees when she was just 14.

Eight years, a physics and maths degree and 160 science education videos later, Tibees’ skyrocketing growth is firming up Hendy’s place within the growing global community of so-called “EduTubers” so much so that she’s halting her PhD and going full-time.

“I’d always thought after I finished my PhD I’d become a lecturer at a university and be able to teach students in that way, but when I started teaching online and was already getting huge numbers, I realised it doesn’t even compare,” the 23 year old says of the difficult decision to withdraw from her physics PhD at Australian National University.

Hendy believes YouTube can be a powerful platform to inspire more young people - especially girls - into science. (Supplied)

“I see how powerful YouTube is as the place that young people now are getting their information. It’s where they’re learning and getting their ideas about the world, so I really want to be part of that movement and inspire more young people into science,” she says.

“You could have a video that you've made in your bedroom getting a million views but you could never reach that many in a classroom. The way it scales is extremely powerful.”

This month, Hendy’s subscribers surpassed 137,000, up from just 2000 a year ago, and her videos – which offer study advice and explore scientific ideas – have been viewed almost 11 million times.

While still a way long way behind the most watched science channels on the platform – like Michael Steven’s Vsauce with 14m subscribers or Dianna Cowern’s PhysicsGirl with 1.2m – Tibees’ momentum is strong.

Part of her appeal may relate to quite a unique trait: her long hair flows more than 1.3 meters down to below her knees. She’s even integrated it into videos to teach scientific concepts, from showing how a Van de Graaff generator affects hair, to how hair can be used to measure acceleration, whether Rapunzel’s hair really could support someone’s weight, and a mathematical equation that computes whether a pony tail will droop.

Toby Hendy has intergrated her unusually long hair into videos to help illustrate scientific concepts. (Supplied)

"My channel has a theme of combining physics and beauty - not only with the hair videos but through the fact that I'm trying to show the beautiful side of physics and maths,” she says.

Her presence is helping address an absence of females in the scientific community, both online and off: just 32 – or 8 per cent – of the 391 most popular science, engineering and mathematics YouTube channels have female hosts, according to a study last year by Australian researcher Inoka Amarasekara. More broadly, the probability of female students graduating with a bachelor’s degree in science-related fields is 18 per cent compared to 37 per cent males, according to the United Nations.

Hendy, who was awarded a Westpac Future Leaders Scholarship in 2017, says boosting female participation is a motivating force behind her channel, aiming to make studying physics and maths seem “less scary”, especially for young girls – a segment of her audience she’d like to grow.

“Girls aspire to what they see. If there are more girls in this space showing that we can be good at physics and maths, then they’ll feel more inspired or comfortable in pursuing it themselves,” she says.

Hendy’s decision last year to devote herself full-time to Tibees was made possible with sponsorship from educational companies including brilliant.org. She also hopes to tap into other funding sources, like YouTube’s $20m “Learning” initiative for education-focused creators announced in October, to improve the production of her videos which she admits are “made on a shoe-string”, often in her bedroom at her family home in Queensland.

Hendy, with a plaque from YouTube when she reached 100,000 subscribers, says YouTube can be a "really hard place for women".

She’s also had to develop “a very thick skin” to deal with the negative viewers comments scattered among the positive, many of which she says are “hard to read”.

“People say things like ‘instead of making physics videos you should be in the kitchen cooking or getting married and letting your husband do the physics’. It can be a really hard place for women to be on YouTube.”

It’s not an uncommon experience. An analysis of more than 23,000 comments in Amarasekara’s study found 14 per cent for female science YouTube hosts were critical compared to 6 per cent for males, and females got more remarks about their appearance (4.5 per cent for women versus 1.4 per cent for men) or that were sexist or sexual.

Hendy says she uses it as motivation, rather than letting it get under her skin, to help change perceptions and increase the pool of female science “EduTubers”, which includes PhysicsGirl, Brain Craft, The Brain Scoop, Geek Gurl Diaries and Gross Science.

And besides that, she takes heart there are far more comments like this posted recently: “It's hard to believe that this year I am liking physics and mathematics only because of you. Thanks a lot!”