Who blinks first – shops or shoppers?

A person experiences Alibaba's virtual reality shopping technology Buy+ at Shenzhen, China in late 2016. (Getty)

When Westfield’s board agreed to a $33 billion sale to Unibail-Rodamco in December, some observers opined that the company had raised the white flag in response to intensifying online competition from new players and changing customer behaviour. Not to mention a good offer.

But others say shopping centres are far from dead and the issue is more complex.

In Western Australia, for example, where the economy is slowly recovering from recession, investment in centres has quietly been speeding up like Usain Bolt on the home stretch.

In a flurry of activity worth about $4 billion – a flurry so competitive one retail analyst labelled it an “arms race” – Perth will see six of its seven major shopping centres get transformative upgrades over the next few years.

Three of the upgraded complexes will include new adjoining apartment developments and almost all of them will get new cinemas – or upgrades – town square-type community areas and “exclusive” boutique retail options to entice shoppers away from their keyboard.

And in what is seen as a critical element in the future of the shopping centre, all the WA centres will include a broad selection of higher-end restaurant options – one even has a micro-brewery – in a bid to encourage more vibrancy in and around the centres.

Scott Nugent, WA divisional development manager at AMP Capital, which is behind three of the centres being upgraded, says its centres were also set to host street parties and pop-up events in a bid to encourage – in shopping centre lingo – “placemaking”.

“It’s a term to describe the way people feel and interact with a space,” he said. “The design and feel – making it feel like a nice place to be. That’s what we really want to encourage. So people can just come for the day – you don’t have spend anything, just be part of it.”

Shopping centres have changed a lot since Frank Lowy opened his first “American style” shopping centre in the Sydney suburb of Blacktown in 1959.

Back then, the main competitor was the local corner store.

Fast-forward to today, and the competition is not on the street – it’s in the cloud.

Even before last year’s arrival of Amazon to Australian shores, online shopping has been gradually chipping away at the margins of Australia’s bricks and mortar stores.

Today, online is shopping with dynamite.

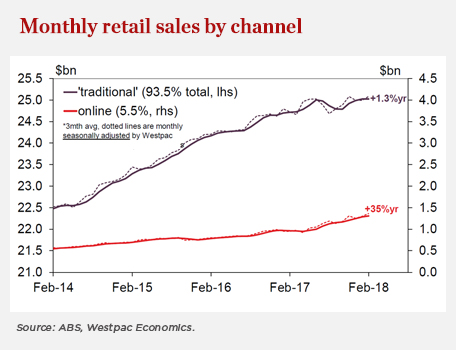

Amid muted overall retail sales growth, Westpac Economics research shows online sales are rising at an annual pace of 44 per cent, increasing its share of the overall market to around 5.5 per cent.

“If you needed a statistic to summarise the disruption currently occurring in Australian retail, it is this: domestic online sales currently account for more than half of total retail sales growth in Australia. A year ago the share was half that, and two years ago it was less than 10 per cent,” Macquarie economists wrote in early March.

While the challenges of publicly listed Myer have been widely publicised – its shares are trading around 40c after never exceeding their $4.10 listing price in 2009 – the department store chain has been far from alone as several bricks and mortar retailers struggle and fall into administration. A commercial outlook report from insolvency firm SV Partners predicts the imminent collapse of 1591 retailers this year - 3.2 per cent of the retail industry, with plus-sized women’s store Maggie T, footwear label Diana Ferrari and discount grocery chain NQR some of the names to fall so far this year.

And even one of retail’s supposed success stories, the Swedish discount fashion house H&M, recorded a global 61 per cent profit fall for the three months to February.

On face value, it looks like a doomsday scenario for Australian retailers, and the shopping centres in which they operate.

An Amazon fulfilment centre in Britain. (Getty)

But this trend has been gathering pace since eBay first hit Australian computer screens more than 15 years ago.

And the multi-billion dollar shopping centre business has watched it coming.

Like Alfred Pennyworth working in the basement for Batman, the brains behind the nation’s hundreds of shopping centres have been beavering away in the dark, thinking up new ways to take on the enemy (Amazon, eBay, Kogan et al).

So what are they doing to force us out of our snug homes and away from our screens to forget about the world of shopping at our fingertips?

Short answer: a lot.

“It’s an evolution,” Roy Gruenpeter, the manager for development at Scentre Group, the owner-operator of the Westfield centres in Australia and New Zealand, says.

“Today, we are creating places that people want to go to . . . a place that is a lifestyle and community hub – not just a shopping centre – that’s the really critical part."

The Australian shopping centre is today attempting to become more than just a place for the consumer to buy things, then leave. The owners of these billion-dollar centres are attempting to turn them into community centre points, a place where a family comes to socialise and relax – the modern-day version of the town square.

And according to retail analyst Brian Walker, three themes are the focus.

“Experience, convenience and community – that’s what it’s all about,” Mr Walker, chief executive of consultancy firm The Retail Doctor said.

“The shopping centre business is at an inflection point. The retail speciality which it relied upon for its growth has been hit hard by technology (online shopping), a change of behaviour and the modern pressure of time.

“And in response the malls are moving away from being a commodity to a broader proposition value.”

And that “broader proposition value” comes through the three themes Mr Walker outlined.

Experience: in the form of new high-end restaurants, cinemas, gyms, libraries and the promotion of special events within the shopping centre precinct. Many international malls feature concert venues, day spas, art galleries and even farmers markets.

Convenience: through the use of technology, data, more open-planned designs and even easier-to-use public transport options.

Community: through the promotion of pop-up events and markets, building of community and medical centres within the shopping centre precinct and apartment developments adjacent or inside the precinct.

And the backers behind the nation’s centres are spending up big. Despite all the doom-and-gloom scenarios, according to global real estate firm JLL, shopping centre retail investment activity in 2017 was the second highest on record at $8.8 billion.

Shoppers take a selfie in front of a life-size sculpture of Benedict Cumberbatch made of chocolate at Westfield Stratford City shopping centre in London. (Getty)

Mr Walker said that was a reflection of the divide emerging in the Australian shopping centre business. To date, banks and other financiers have been watching closely but facing mostly isolated problem areas. In its full-year results in November, Westpac for example noted that its retail trade portfolio – which included food retailing, motor vehicle retailing and services, and personal and household good retailing – comprised $11.5 billion of lending and the percentage that was impaired fell to 0.31 per cent in the six months to September 30, from 0.4 per cent six months earlier. The percentage graded as “stressed” however increased.

Mr Walker said huge A-grade centres, such as Bondi Junction in NSW or Pacific Beach in Queensland or Chatswood in Victoria which recently opened a Lego discovery centre in its complex – were in the “too big to fail” category, almost immune from the day-to-day retail challenges.

It was the smaller shopping centres, the ones with 100-200 stores and anchored by a discount department store, that were more under threat.

He said Unibail-Rodamco’s takeover of the Westfield business was case-in-point.

“That’s a player (Unibail) with a big capital budget coming in to continue with this type of big-ticket investment,” he said.

“And over the past few years it has been a very steady change (to this new model).

“But it’s no coincidence that it’s really gathering pace now.”

Despite the confidence of the companies behind new developments, doubters remain.

Retail analysts have questioned the viability of shopping centres offering up what was once prime retail rent to community-focused facilities, which pay less.

Coming on the backdrop of a depressed retail market, with heavy-hitters such as Solomon Lew’s Premier Investments pulling big name retailers out of shopping centres until they “get competitive” on rents, some are questioning if there will be enough quality retailers left to fill them, and entice shoppers in.

And with billions being invested – in WA all at the same time – there are further questions over the demand from consumers, despite the new bells and whistles on offer.

“It’s going to be very interesting,” West Australian-focused retail analyst Darryll Ashworth said. “They (the shopping centres) will be popular, no doubt. But every second day there are stories of retail decline, and I’m unsure about it all."

The final piece in the puzzle for the future of Australia’s shopping centre business takes from the adage: “if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em”.

The online world has devoured retailer’s margins, so now the shopping centre world is attempting to use technology to get back in the hunt.

The use of big data, artificial intelligence and augmented reality have long been touted as areas the shopping centre business could leverage to create more enticing experiences for the shopper.

Chatbots, which act as a mobile information desk answering questions such as “where can I find the Polo Ralph Lauren store?”, and directing consumers where to go within the centre, are another area of development.

Geofences are also becoming increasingly common in US malls. Using GPS, shopping centres create virtual boundaries that detect shoppers when they move into the area. Once inside, they can receive notifications on their mobile devices about parking, free Wi-Fi and special events or offers.

Westfield has gone on the front foot, creating tech subsidiary OneMarket – which was itself created on the back of Westfield Labs – a Silicon Valley based business focused on developing new retail technology.

However the company, labelled as “mysterious” by The Australian Financial Review, has yet to reveal any firm business plan. Westpac Wire’s requests for an interview with the company were unanswered.

Again, there are sceptics, with trials of virtual assistants, augmented reality and similar technologies receiving lukewarm responses during trials in US malls.

But despite all the complications of the shopping centre business, and all its bells and whistles, according to Scentre Group’s Roy Gruenpeter, his confidence in the future of Australian centre comes back to one simple element.

“We’re humans,” he said.

“We do thrive on personal contact. And the modern shopping centre is about providing the environment for that to happen.”

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Westpac Group.