More to wages growth mystery than let on

The relative lack of jobs being filled by men when more have been joining the workforce is weighing on wages growth. (Getty)

Much has been made of a handful of potential reasons for why wages growth is holding at low levels globally despite strong jobs growth and low unemployment.

For economists, central banks and academics, it’s arguably become one of the greatest economic questions of our time.

But we may be focusing on the wrong issues.

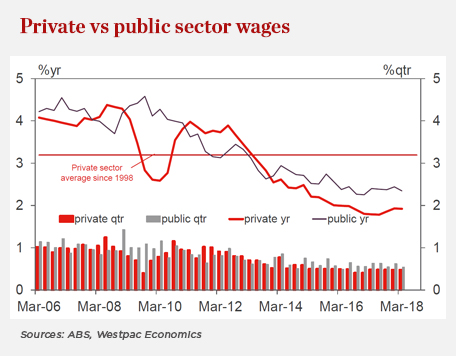

Last week’s official data for the first quarter showed little change, wages ex-bonuses increasing 0.5 per cent or an unchanged 2.1 per cent over the year, and just 1.9 per cent for private sector workers, in line with inflation.

As I wrote last week, this came despite the clear improvement in the labour market in recent times, whether that’s measured by total employment, full-time employment, hours worked, unemployment and even underemployment. Also, various business surveys suggest firms are starting to find it hard to recruit and the market has absorbed the larger than usual recent 3.3 per cent rise in the minimal wage.

Yet we are still waiting for a meaningful lift in wage inflation.

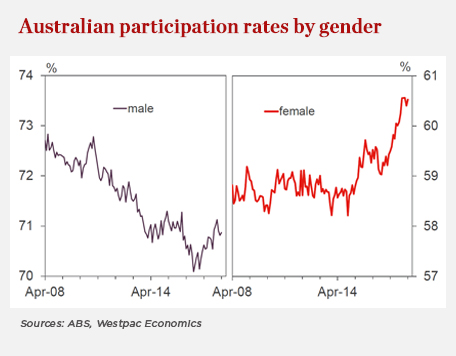

There have been a lot written about the impact of the growth in employment in services sectors, which has been matched by rising demand for female labour and a near record-high participation rate.

But less has been discussed about another issue keeping the unemployment rate higher than it otherwise would be: the relative lack of jobs being filled by men. This is problematic because more men have been joining the workforce – putting a halt on the longer run decline in the male participation rate and creating more competition, weighing on wages.

Another issue often spoken about weighing on wages growth are broader macro impacts, such as globalisation, technology disruption and increasing competition, and companies investing less in fixed assets that require lots of people. But in reality, these are what you might call stylised facts in that there is not a lot of hard data to support the assertions.

A look at wages and the labour market conditions in different states goes to the heart of this.

In Victoria, things are behaving as you would expect, wage inflation lifting from the recent lows of late 2016 on stronger broader conditions. But it’s a different story in NSW, where wages are significantly underperforming the meaningful tightening in labour market conditions. Despite a significant fall in underemployment, NSW private sector wages continue to languish around 2 per cent annually, which is dragging on the national figures given it is the largest state.

In a November speech, Reserve Bank of Australia Governor Philip Lowe surmised that businesses in many advanced countries were not “bidding up” wages in tight labour markets as they had in the past, partly because of a “laser-like focus on containing costs” amid the pressures of increased competition.

But if the large macro forces such as globalisation and greater competition were behind the underperformance in wages, why are they having such an uneven impact across two similar states in the same country?

Part of the answer may well be that the most powerful structural force is the widespread reluctance of firms across the economy to pay larger wage rises. Companies may point to several reasons for this, but the reality is staff are often one of their biggest costs and can be a release valve to smooth out rates of return through economic cycles. While the economy is chugging along, annual growth moderated to 2.4 per cent from 2.9 per cent in the December quarter and demand is mixed across industries.

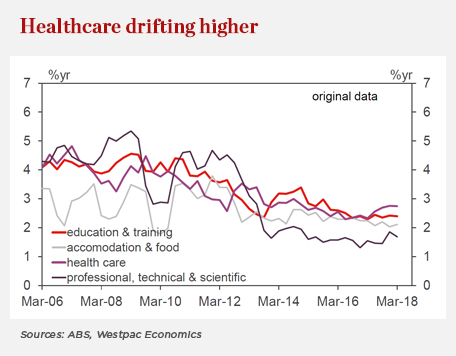

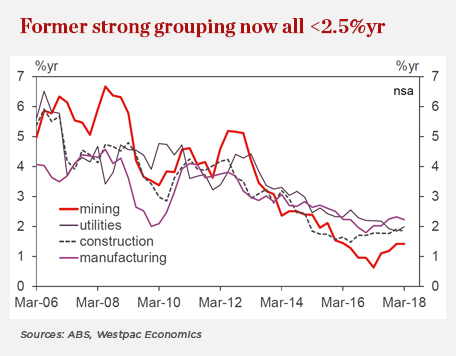

As the March quarter wages data showed, inflation in the mining sector has improved off a low base but remains the slowest at 1.4 per cent. The fastest for wages were again health care, arts & recreation, and education and training – industries that have experienced strong employment growth but often have a high proportion of females and lower paying jobs.

Last week, RBA assistant governor Guy Debelle spoke of the risk that it may actually take a lower unemployment rate than they expect to “generate a sustained move higher than the 2 per cent focal point evident in many wage outcomes today”.

These comments follow the RBA’s downgrade this month of its unemployment outlook, seeing it falling to 5.25 per cent from 5.6 per cent by June 2019 – a year later than the June 2018 target forecast in February.

For the Westpac Economics team, an equal risk to the outlook for wages growth is that a larger than expected fall in unemployment may still not generate the “gradual” lift in wages the RBA is expecting. And there is the risk that even if we get stronger than expected employment growth, particularly from services sectors, then the unemployment rate may not fall as hoped due to rising female participation.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Westpac Group.