Follow the food: farming rethink in Asian century

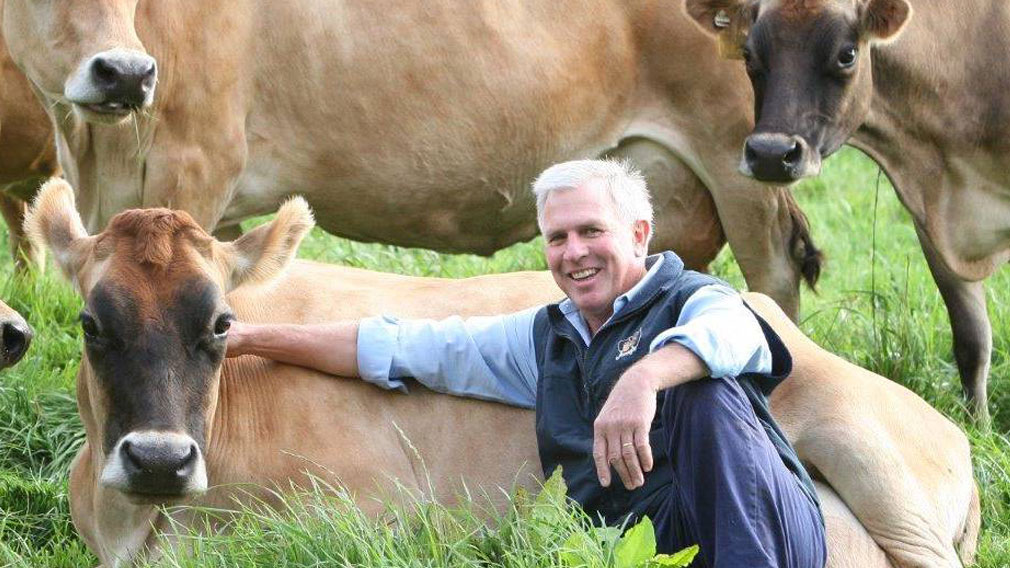

Westpac's head of agribusiness, Steve Hannan, says Australia needs to build on its status as a "food destination" to capitalise on the expected lift in tourists, particularly from China. (Getty)

Australia’s agricultural industry has never been so powerful.

According to the latest national accounts figures, it’s become the biggest contributor to gross domestic product and fastest growing sector after production in 2016-2017 expanded a massive 23 per cent to $62.8 billion.

Bulk commodities like iron ore may remain a major income generator for the nation, but unprecedented international demand for our quality food and fibre contributed $50bn of exports in 2016-17, or just below 14 per cent of Australia's total.

And I take my hat off to all Australian farmers for achieving these incredible results, as we celebrate National Agriculture Day today.

But we can – and need to – do even better.

Steve Hannan explains how he believes Australia can play a leading role in the looming “food revolution” as the world gets hungrier.

I often hear Australia being called the “food bowl of Asia”, and it’s true that the growing affluence of the Asian middle class – and their preference for high quality produce – has contributed significantly to the rise in exports.

Yet our farmers produce enough to feed about 61 million people. That sounds like a lot until you consider Asia has a population of about 4.4 billion, and Australia’s population is projected to reach up to 48.3 million by 2061. Indeed, the world's population is expected to hit 9.6 billion people by 2050.

As a big country with around two arable hectares per person – the highest ratio in the world, according to Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations – and the soil and climate to produce a variety of food all year round, we have masses of opportunity. But to make the most of this, we need to think differently.

The standout areas are our approach to exports, and making our cities “smarter”.

We’ve traditionally had a strong focus on sending our agricultural produce off shore and around two thirds of our nation’s farm production is exported, serving us very well.

While exports will remain important, I believe we’re missing a trick in what we can do with our produce on-shore. If we prepare now, there’s upside from the massive projected uptick in tourists, particularly from China, if we seriously build our emerging status as a “food destination”.

During a recent trade delegation to China I hosted last month, it became ever more apparent how much importance Chinese locals were placing on the provenance of their food – they want to understand the stories behind it, know the farmers, see the farms, the cattle, the sheep, and understand how it’s grown.

Steve Hannan (centre) with guests on a Westpac-hosted trade delegation to China last month.

When coupled with the steep incline of inbound tourism, this creates a really big opportunity – particularly in regional, rural and remote Australia – for the development of more small clusters of food destinations.

We’re expected to welcome 15 million tourists in 2026, up 75 per cent from 2016, and they’ll spend $75.8bn, according to Tourism Research Australia. An extraordinary $26.2bn of that is projected to come from almost 4 million people travelling from China. That’s up from 1.3 million last year. Already, up to 90 direct flights arrive in Australia from China every week.

As tourists explore Australia, they’ll follow the food. Farmers will be able to tell their story as they sell their product locally. And local motels, pubs, butchers, chemists, newsagents, hamburger shops and bakeries will also benefit (and businesses should start thinking about how these tourists may wish to pay, for example through mobile payment giants like Alipay).

Yes, pockets of food destinations already exist. But the noise needs to grow, particularly in China. We need to talk it up. More Australian farmers must go to China, not just to sell their product, but to build awareness of what Australia has to offer and bring more Chinese and Asian tourism inbound to hit the food trail.

In my mind, success would be dropping the proportion of agricultural products exports closer to 50 per cent from 65 per cent, as we sell more produce to inbound tourists. We will still feed the same, growing market, but instead of us exporting to them, they will come to us. That will have the added benefit of reducing exposure to externalities, such as fluctuating international pricing, distribution, exchange rates and international politics.

We also need to turbocharge making our cities smarter.

Despite the vastness of our country, almost 70 per cent of our population lives in cities, many of whom have never set foot on a farm. And yet our cities have great potential to add to our food production.

Indoor horticulture for vegetable crops, known as “vertical farming”, “skyscraper farming” or “aero farming”, has emerged in cities around the world, made possible by cheaper and more sophisticated technology.

In China last month, the incredible 250-acre Sunqiao Urban Agricultural District is to be constructed among the soaring skycrapers of Shanghai from next year. It will have towering vertical farms that will feed almost 24m people – the population of Australia!

To put that in perspective, New Jersey in the US has today’s largest indoor vertical farms, at 70,000-square-feet and capable of producing up to two million pounds of vegetables and herbs. Japan and Canada are also leading the way.

For Australia, the potential to add to the production pile from traditional farming is huge.

As a long-time agri-banker seeing farmers’ navigate challenges and opportunities over time, I believe Australia can play a leading role in the looming “food revolution”. The world is only getting hungrier, that we all agree on. But it’s time to discuss doing and thinking about it differently.