‘Carmageddon’ may be closer than think

A passer-by captures the Mercedes Benz F 015 self-driving car in Amsterdam as it’s presented in Europe for the first time in 2013. (Getty Images)

Earlier this year Ford, arguably the biggest name historically in the auto industry, paid US$1 billion for a majority stake in Argo AI, a start-up firm specialising in artificial intelligence (AI) for self-driving cars.

The move, according to former chief executive Mark Fields, was all about “strengthening Ford’s leadership in bringing self-driving vehicles to the market in the near term”.

It was an historic moment for the company which pioneered the production line in the “motor city” of Detroit in the 1920s. But the Argo AI deal around 100 years later wasn’t enough to save Fields, who in May abruptly left and was replaced with Jim Hackett, who the company labelled the “right CEO to lead Ford during this transformative period for the auto industry”.

Dubbed “carmageddon”, the rise of electric and driverless vehicles is increasingly leading to predictions that the internal combustion engine and steering wheel’s days are numbered. And it’s not just the likes of Tesla incumbents are competing with but technology giants such as Google and Apple. A list of corporations working on driverless cars and trucks is a who’s who of the car and technology sectors.

“I think the late 2020s and early 2030s will be the tipping point,” says Scott Warburton, an analyst in industry analytics and insights, Westpac Institutional Bank (WIB). “One day, and it won’t be too far away, just about every car you can buy today with an internal combustion engine will have an electric motor instead.”

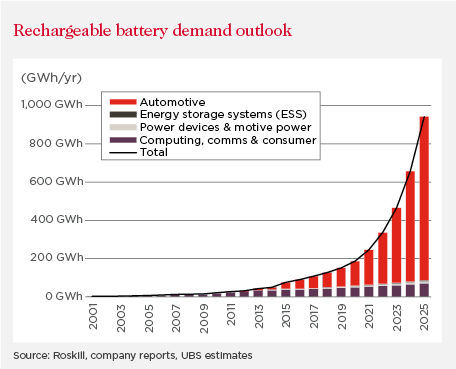

Just last year, two million electric vehicles, or EVs, were sold worldwide and, according to the International Energy Agency that could grow to 70 million by 2025. Further out, investment bank Morgan Stanley predicts EVs will reach parity with cars powered by internal combustion by 2050.

Forces are already well and truly at work to make this reality: The UK recently joined France in banning fossil fuel cars by 2040 while China – the biggest market for EVs partly due to government incentives -- has also flagged banning petrol and diesel.

In Australia, the market for EVs has some catching up to do. While Australian drivers have embraced hybrid vehicles, with 12,000 sold in 2016, sales of purely electric vehicles slumped by 90 per cent, with only 219 EVs sold nationwide in the year.

The first issue, according to Westpac’s Wayne Gagel, is the lack of choice among EV models, and their pricing. “You have four or five models available and most are at the high end of the market, from manufacturers like BMW and Tesla,” says Gagel, senior analyst, industry analytics and insights in WIB. “And then there is the range anxiety among Australian drivers, and that makes them nervous about EVs.”

While the average Australian driver travels less than 30 kms a day, long-distance driving isn’t uncommon in such a large continent and awareness is low of infrastructure such as re-charging stations.

The Australian Energy Markets Operator (AEMO) estimates that EVs will go from using only 14 gigawatt hours (GWh) of power in 2016, to 6555 GWh annually by 2035. This has led to concerns about what plugging in a lot of vehicles all together might do to demand on electricity supply.

Change, however, is inevitable as EV prices likely fall over time and electric autonomous vehicles hit the market.

A futuristic scene from renowned TV show The Jetsons, originally aired in the 1960s. (Getty Images)

In Melbourne, motorways owner-operator Transurban is testing “Level 2” autonomous vehicles in a three-phase trial over two years in collaboration with four car makers, VicRoads, Victoria Police and the RACV. Where Level 5 vehicles are fully autonomous, Level 2 vehicles have some automated functions, such as controlled speed and steering, and are currently on the market.

“The trials are specifically on our infrastructure and in our motorway environment,” says Jeremy Nassau, Transurban’s Senior Manager of Strategic Initiatives. “The aim is to understand the unique aspects of how these vehicles use and interact with our infrastructure, so we can optimise the changes we need to make.”

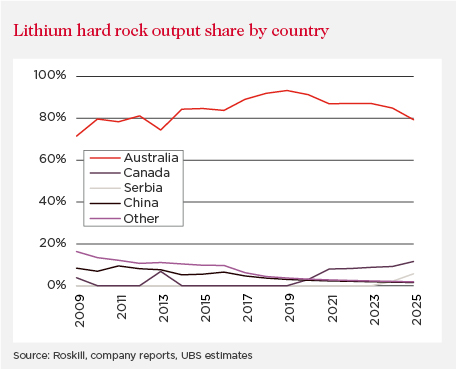

Credit Suisse’s Australia-based analysts in July labelled autonomous vehicles “revolutionary”, impacting fuel and electricity demand, transport, the provision of insurance and healthcare. There was a “high likelihood” of employment “impacts” across the transport sector, where other experts believe driverless long-haul trucks could be one of the early growth areas. On a brighter note, growing demand boded well for Australia’s materials industries, specifically miners of lithium, nickel and cobalt that is used in batteries.

As UBS analysts told clients in September after visiting China and Korea: “Lithium ion battery boom is coming; raw material demand to soar.”

The impact of driverless cars on government road funding and revenue could be significant given substantial income derived from registration, licensing, traffic fines and fuel taxes. Already, debate is occurring about road funding for the AV era given the looming need for new investment in roads, communications infrastructure for vehicle connectivity and specific lanes for AVs.

In a recent article, PwC partner and infrastructure lawyer Owen Hayford argued that Uber and other ride providers were currently “capturing the value” from the public investment in road infrastructure, which governments could do by imposing road user charges on everyone that consumes public road capacity.

Accenture’s Craig Ridley says the transition to AVs also presents major challenges to banking and insurance, where some products will cease to be relevant, others will change, and new ones created.

“For example, we will see the demise of individuals taking out car insurance,” says Ridley, who heads up the firm’s innovation and fintech agenda. “Companies which provide autonomous vehicles will be the ones taking liability, so where will they get that from? Will large fleet managers turn to traditional insurers, or will the car companies move into providing insurance?”

AVs will also transform the urban commute, creating mobile offices where people can work instead of concentrating on road traffic. This may have a knock-on effect on house prices, with inner suburbs losing some premium value as outer suburbs become more attractive. “There is potentially a major rebalancing of (banks’) mortgage books and valuations coming up in the next decades,” tips Ridley.

Westpac’s Warburton, however, sees opportunities too, citing the use of high tech sensors and microchips for data processing in AVs. “Australia is losing its car manufacturing, but that could still leave some significant research and development opportunities,” he says. “Furthermore, Australia is well positioned to benefit given our strong resource reserves, including lithium and nickel, and our highly skilled workforce which can support the development of emerging technologies.”

After all, as Gagel observes: “Where else do cars have to deal with traffic hazards as serious as kangaroos?”