What history tells us about equity bear markets

Traders at the New York Stock Exchange. (Getty)

Global shares may have rallied off this year’s lows, but the lessons from previous bear markets suggest there’s a risk of further losses before a sustainable price recovery sets in.

A bear market is commonly defined as a price fall of 20 per cent or more off a recent peak. By that measure, the US benchmark S&P 500 index entered one in June. In fact, the index posted its worst first-half performance in over half a century, losing nearly 24 per cent at its nadir.

The declines were driven by an aggressive shift in policy by major central banks to fight inflation.

The US Federal Reserve has increased interest rates dramatically – by a total of 2.25 per cent since March. Those hikes came in response to stronger and more persistent price pressures than expected, but markets are concerned that the rapid tightening might tip the economy into recession.

However, the S&P 500 has rallied as much as 16.8 per cent off its June lows as investors pared back their expectations of the extent of future Fed tightening.

There is considerable speculation as to whether the rebound marks a change in direction for the market, or is just a bear market rally which will be unwound on the way to a new trough. This will very much depend on the path of inflation and interest rates, and how the US economy reacts to tightening financial conditions.

But we can also look to previous bear markets for some pointers.

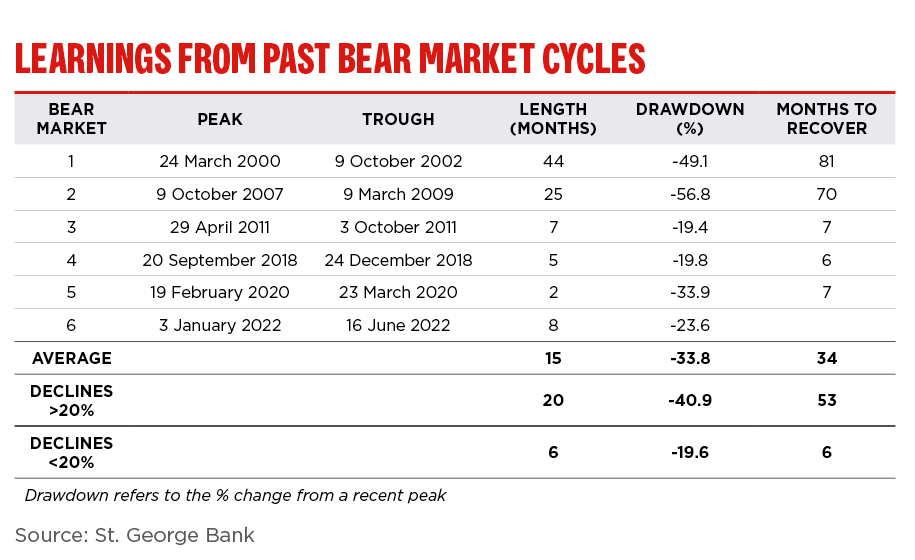

Since the turn of the century, the S&P 500 has experienced four bear market episodes, including the latest one. There have been two pullbacks where the decline was just short of the 20 per cent threshold but are still worthy of inclusion in our analysis.

Of those, the average bear market lasted for 15 months, during which the S&P 500 declined by 33.8 per cent on average. That would suggest the current bear market may have further to run, having declined by 23.6 per cent over seven months.

The analysis also showed that it took an average of almost three years for equity losses to be recouped following a bear market.

Additionally, it’s a common feature of a bear market that there’s a price rally before the index reaches its ultimate low point. These so-called bear market rallies can make it difficult for investors to judge whether the market has truly bottomed out.

Each bear market we examined experienced at least one rally of 5 per cent or more before reaching a trough. The biggest bear market rally saw a 24 per cent bounce before retreating to a fresh low.

So what implications does this have for the Australian market?

The benchmark ASX 200 index tends to be highly correlated to the US – especially in its reaction to global macroeconomic factors, which have been a key driver of equity markets in 2022.

However, the Australian market has outperformed Wall Street so far this year, mainly thanks to its heavy weighting towards energy and resources companies, which have experienced considerable tailwinds from high commodity prices.

Investor perceptions that the local economy will be able to dodge a recession, despite a series of rate hikes from the Reserve Bank of Australia, may also help explain that outperformance.

On August 23, the ASX 200 closed 8.7 per cent below its peak in August last year, after being as much as 15.7 per cent lower in mid-June, and as such is yet to enter a bear market.

However, the trajectory of US share markets will still be a critical factor for the outlook of Australian (and global) share markets, and we cannot rule out a domestic bear market should global and domestic economic conditions deteriorate considerably.

To read the full report, click here (PDF 1MB)