New design of ‘fresh start’ shows results

Helen Black created Australia’s only graphic design studio inside a prison in a bid to help reduce recidivism rates. (Emma Foster)

Helen Black never thought she’d be spending time behind bars.

But now she couldn’t think of anything more worthy.

Black is not a prisoner. Rather, she’s taking a novel approach to help restart prisoners’ lives by putting real businesses on the inside to give inmates a better chance of employment on release.

Just over a year ago, she opened “Barbed Design” inside Borallon Training and Correctional Centre, near Ipswich, Queensland – a graphic design studio that employs around 15 prisoners, trained and overseen by qualified digital graphic design professionals, who serve clients on the outside.

The studio, modelled on a similar concept set up within the United Kingdom’s Coldingley Prison in 2005, is one of a growing portfolio of “businesses behind bars” created by workRestart, a social enterprise that matches business owners with a reliable, low cost prisoner workforce.

“Our goal is to give prisoners training and experience in digital industries – not just in graphic design, but in other related fields – to put them on a pathway to secure employment on release,” says Black, who works in workRestart’s industry engagement team and one of nine Australians to be named Westpac Social Change Fellows earlier this year.

Operating just like a design studio on the outside, Barbed Design’s employees – who go through an interview process – have a busy schedule of projects for more than 20 clients.

“The people we work with don’t make excuses for their behaviour. They own their past, understand the impact it’s had on families and communities and genuinely want to change,” says Black, who’d previously worked in small business and mentoring entrepreneurs.

“Our motto is ‘your past doesn’t have to define your future’. So, whether they’re convicted of theft, drugs, break-and-enter or yes, even murder, if they say, ‘I want a different future’, they’re welcome to participate.”

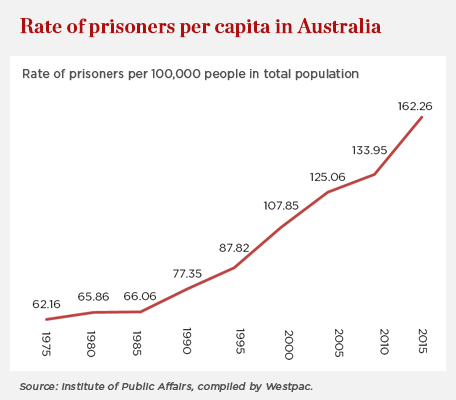

Black’s initiative comes at a time when the number of prisoners is on the rise, increasing for the sixth year in a row last year, to 41,202 at June 30, 2017, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics. This was up 6 per cent from the previous year and 51 per cent higher than just a decade before, contributing to a cost to Australian taxpayers estimated by the Productivity Commission at more than $3 billion a year.

Australian prisons are the fifth most expensive among 29 countries in the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development at nearly $110,000 per prisoner per year, compared with an OECD average of $69,000, according to a study last year by the Institute of Public Affairs.

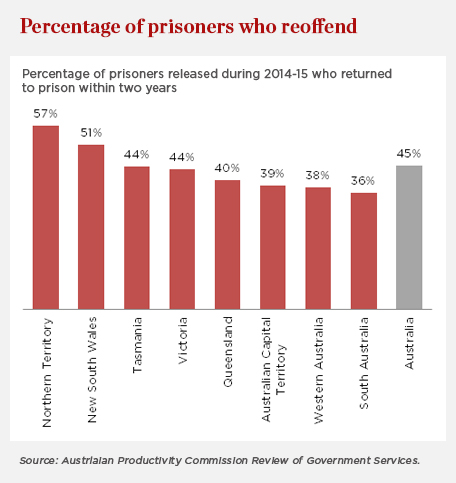

For Black, the most worrying issue is the high rate of released prisoners returning to prison – known as recidivism – with 45 per cent of prisoners in Australia released during 2014-15 back behind bars within two years.

Black says the most common hurdle for prisoners upon release is being “locked out” of employment due to lack of education, experience or having a criminal record. “Hundreds of studies show the single most important factor in reducing re-offending rates is through finding employment, but this is the thing many prisoners struggle with the most,” she says.

Working while incarcerated is not a new concept but, as Black explains, jails have historically only offered work using traditional skills, like metal- and wood-work, limiting employment opportunities on the outside amid rapid technological change and developments.

“The digital side of things is really critical for most industries these days, which is why that’s where we are focused,” she says.

Although early days for the studio, Black says signs of success are already starting to show, citing the story of one employee serving a sentence for a very serious offence she’s unable to disclose.

“He’s grown up surrounded by crime and he’d always been told he’d only ever do a trade. But he’s also incredibly keen to learn,” she says.

“He’s now working on 3D modelling and he’s like a duck to water. He’s incredibly good on computers. And he’s told me he wouldn’t have had any opportunity to have found this path without Barbed being there.”

“But what's been most amazing is that he's recently asked what he can do to help teach others. That was a real turning point – from a focus on self to a focus on others. That to me is a true measure of success.”