Economists eye what federal budget may bring

Treasurer Scott Morrison during question time a day after delivering the 2017 budget. (Getty)

In May 2005, then-Treasurer Peter Costello saved a big carrot for the back half of his budget speech.

“Australians deserve the lowest possible taxes consistent with responsible budget management and the provision of efficient government services,” he told parliament, ahead of detailing a fresh $21.7 billion of personal income tax cuts over four years as cash from the mining boom rolled in.

More than a decade on, personal income tax cuts are again widely tipped to be a key feature of next week's federal budget.

Depending on the details, it could mark the first reduction in headline marginal tax rates for individuals since 2010-11, when the rate for workers earning between $80,001-$180,000 dropped to 37 per cent, from 38 per cent. (Albeit the real top marginal tax rate also reduced last year after the budget repair levy was removed.)

In a research note today, Westpac chief economist Bill Evans said reducing the tax burden was likely to be one of the key budget themes flagged by the government, particularly for low and middle income earners, alongside infrastructure spending.

“One option, among many possible options, is to lower the tax rates by 1 percentage point for each of the three lowest income brackets, namely to: 18 per cent for the $18,201 to $37,000 bracket; to 31.5 per cent for the $37,001 to $87,000 bracket; and to 36 per cent for the $87,001 to $180,000 bracket; while leaving the top bracket of $180,001 and above unchanged at 45 per cent,” he said.

“The estimated annual cost of such a measure is $5.7bn. This is the figure we have factored into our calculations for the years from 2019-20, with an assumption of a partial phasing in of this measure in 2018-19.”

Another option, as noted by JPMorgan’s economists this week, was to deliver personal income cuts by increasing the thresholds for lower income taxpayers to address “bracket creep”, rather than by reducing rates within the income thresholds.

As the biggest source of revenue, personal tax rates have however proved difficult to materially reduce in recent times amid turbulent economic and political conditions.

In contrast, the spoils of the mining boom fired up several rounds of planned and actual reductions. In 2006, Mr Costello moved to reduce marginal tax rates at the “upper end of the income scale”, claiming the Coalition government had lowered marginal tax rates at the lower end of the income scale since 2000. Two years later in 2008, Labor Treasurer Wayne Swan promised to deliver another $47bn of personal income tax reductions over four years aimed at low to middle income earners, arguing tax cuts had long been “skewed to those already doing very well”.

Then the global financial crisis hit, taking a major toll on the budget and debt levels.

However, in the longer term, much has changed since the introduction of a federal income tax in 1915 – on top of state income taxes – to help fund the First World War. For example, the top marginal tax rate was 75 per cent in the early 1950s compared to 45 per cent today, not including the Medicare levy, according to Treasury.

With the government already confirming it would scrap the $8bn increase in the Medicare levy to help fund the National Disability Insurance Scheme, Mr Evans said other budget themes would likely include the environment, health and aged care, and education, such as the continuing implementation of “Gonski 2.0”. “The net impact of new expenditure measures is likely to add to total budget expenditures. To our knowledge there has been no talk of significant offsetting savings measures,” he said.

The government also remains committed to the remaining element of their 10-year company tax cut package, a move which progressively reduces the rate from 30 per cent to 25 per cent by 2026-27 for all companies but has divided political parties.

UBS economist George Tharenou added that other likely policy announcements could include revisions to the research and development tax offset, withholding tax for foreign investors in stapled structures, and multinational tax avoidance. He added gross debt would likely improve better than expected in the December Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook (MYEFO).

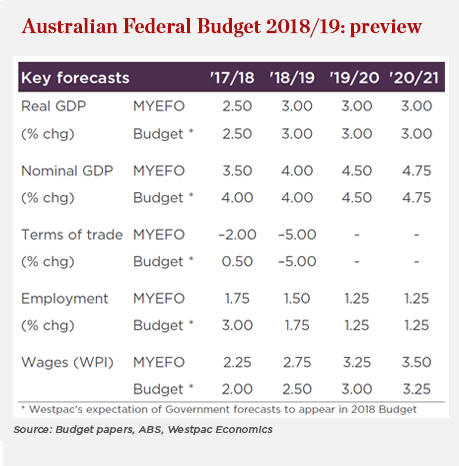

The government enters the budget in an improving position relative to expectations in MYEFO due to strong employment growth and higher commodity prices. Westpac Economics predicts the underlying deficit for 2018-19 to be $15bn, a $5.5bn upgrade on MYEFO, or $11.5bn across four years. The budget is still tipped to return to surplus in 2020-21.

JPMorgan economists said: “For the first time in many years Australia’s Federal Treasury enters this budget season with an improved fiscal position, thanks to a rebound in the terms of trade and nominal GDP growth, as well as increased pay as you go receipts and reduced welfare payments following last year’s employment boom.”

In terms of risks going forward, Mr Evans said economic growth could fall short of budget expectations of real GDP expanding at 3 per cent each year from 2018-19 to 2023-24, above Westpac Economics’ forecast of 2.7 per cent and 2.5 per cent for the next two years. Another is the upcoming Federal election and the potential budget impact of spending promises, he said.