Fed, RBA rates flip to linger this time

New US Federal Reserve chairman Jerome Powell at a news conference announcing the quarter-point increase in interest rates. (Getty Images)

March 21, 2018 may be remembered as an otherwise normal day for most. But for many market participants, it will be etched in their memory as historically important for Australian and US monetary policy, with flow on effects to the broader economy.

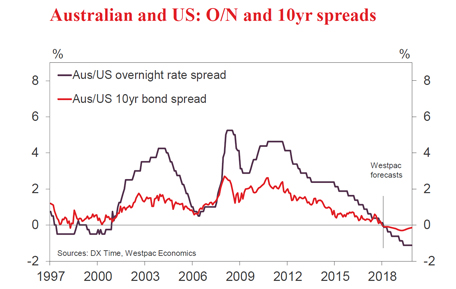

For the first time in almost two decades, today the cash rate differential between our two nations turned negative after the Federal Reserve’s rate hike. That is, the US’ fed funds rate at 1.625 per cent is now above our RBA cash rate of 1.5 per cent.

Related to this shift is an equally significant negative differential between our 10-year government yield and that of the US. Currently it sits at negative 0.15 per cent, a near record back to the early 1980’s.

A negative cash rate differential is rare. It occurred in the 1970s and 1980s. But since the introduction of inflation targeting in Australia in the mid 1990’s, it’s only occurred twice in the late 1990’s.

What sets this occasion apart is the scale of the negative differential expected and its longevity. On our current forecasts, the differential will widen from negative 0.125 per cent today to negative 1.125 per cent by June 2019.

Even when the RBA begins to hike rates – we see this occurring no earlier than mid-2020 – they are likely to be limited to a couple of 0.25 per cent increases. Hence, a rate differential of negative 0.625 per cent or more should be seen out to 2021.

Why is policy so different in the US to Australia?

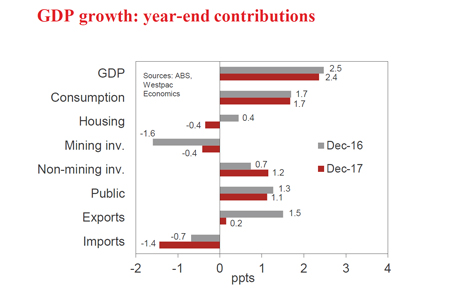

Long story short, their economy is growing well above “trend”, whereas ours is not. Indeed, Australian GDP growth has consistently printed below trend – or potential growth – for the past five years.

In part, the outperformance of the US economy comes from a delayed recovery from the GFC: consumers have only been willing to spend freely for the last four or so years; and for business, it has really only been the past year.

Looking ahead, the primary supports for growth in the US will be the tax and spending initiatives that have been passed by Congress in recent months. These policies are of a scale not normally seen outside of a recession. In this instance, they come at a time of low unemployment and (slowly) accelerating wages. The result should be strong growth and accelerating inflation. That will be met by higher interest rates from the Federal Reserve.

As a comparison, Australia never had a recession post GFC, hence pent-up demand was of a much smaller scale and released earlier. While there have been a number of one-off factors that have led to softer growth in Australia since, the end of the mining investment boom for one, now, the subdued outcomes that are holding Australian GDP growth below trend are at the heart of our economy.

Simply, the consumer remains reluctant to spend. This is not because they doubt their job prospects, but rather because they desire to pay down existing debt which, relative to the economy, remains at historic highs. This is also holding back business investment because a large portion of investment depends on the consumers’ willingness to spend.

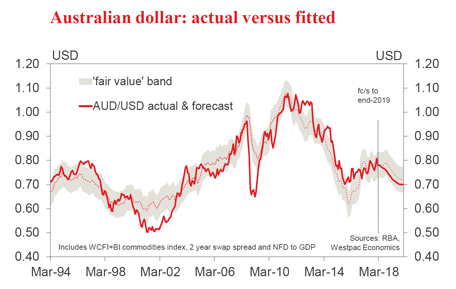

What does a negative rate differential mean? Chiefly it is a lower Australian dollar, a positive for our economy.

When we forecast the Australian dollar, the two critical factors we incorporate are the relative level of Australian interest rates versus those in the US and commodity prices. That we foresee a sizeable negative differential through 2018 and 2019 is a strong justification to believe that the Australian dollar will depreciate from its current level of US77c to US74c by the end of this year, then to US70c by September 2019 – where it should remain to the end of that year. Commodity prices are also expected to fall over the period, reinforcing the Australian dollar downtrend.

It’s worth noting though that there’s much at play in global markets at any given moment. One example of this has been the stubbornly weak US dollar of early 2018, when the allure of higher interest rates was more than offset by concerns about the growing size of the US government’s fiscal deficit. Heartened by history, we continue to believe the rate differential will win out. Still, there are always risks.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Westpac Group. This article is general commentary and it is not intended as financial advice and should not be relied upon as such.