'Male preserve invaded': bold past steps laid path for more

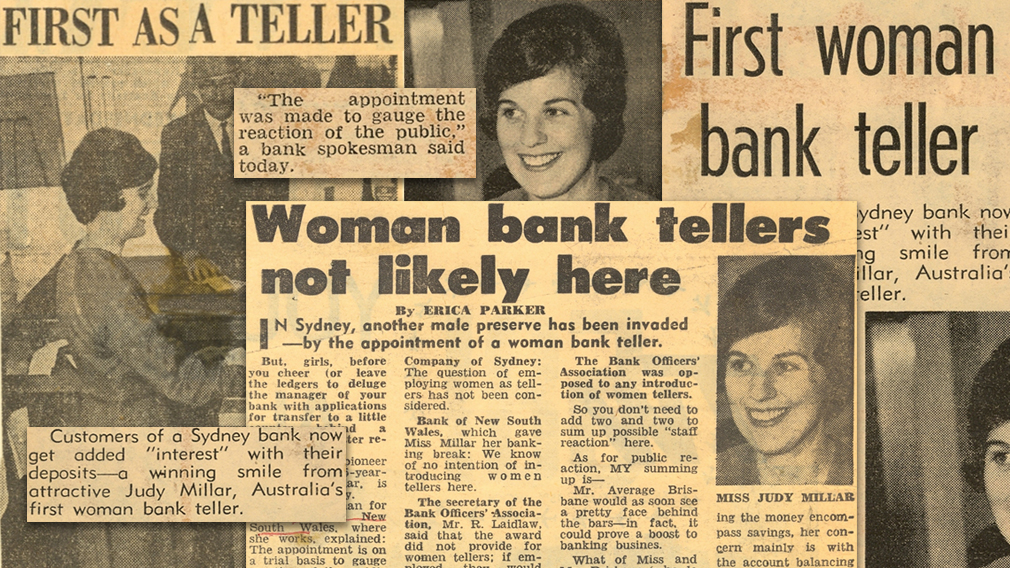

Judy Millar made national headlines when she became Australia’s first woman teller in October 1961, at the Bank of NSW (later Westpac). (Westpac Archives)

In some ways it’s a little disheartening to know after so many years of activism there’s still a need to “break the bias” around gender equity, hence it’s the theme of this year’s International Women’s Day.

But when I look through Westpac’s private archives, I can’t help but think how steep the societal hill is that Australia is still climbing.

As strange as it seems now, the bank’s archives show not one woman was employed in its first 80 years.

In 1898, among a staff of around 1000, the first two women joined – Edith Lamb and Tennyson Beatrice Miller, employed as ‘lady typewriters’.

Since then, it has taken a raft of incremental and, in many cases, audacious steps over decades to even the field for women working in the bank (now making up more than half of its staff) – often breaking new policy ground that other organisations across the country followed.

While each step attracted attention in various quarters, the first to trigger national headlines was when a woman began serving customers in October 1961. Judy Millar became a teller at the bank’s Wynyard branch in Sydney – at first on a trial basis to “gauge the reaction of the public”. Until then, women – who made up around one third of staff – had only been employed in behind-the-scenes clerical roles.

Under the front-page headlines on Millar’s appointment – some of which splashed, ‘Raised interest at the Bank of New South Wales’, and others said “another male preserve has been invaded” – Millar, who had joined the bank nine years earlier, was compelled to explain through the media she was fully capable of the role, both physically and mentally, and that most of her customers managed to overcome their scepticism.

How progressive this was compared to 60 years earlier when the first ‘lady typewriters’ started.

Those ground-breaking women, Lamb and Miller, were required to arrive and depart their head office workplace at different times to the male employees, and their office was sectioned off from the men. This was because they were considered a distraction – apparently the wives of senior bank officers were concerned about temptation, and the bank itself was worried about the reputational effect of having female employees.

Needless to say, both women were perfectly capable workers, Miller remaining with the bank until she retired in 1939, having successfully lobbied senior management to set up a superannuation fund on equal footing with that of her male counterparts – the first such employee super fund of its kind in Australia.

The outbreak of World War One in 1914 pushed up the number of women employed by the bank to around 15 per cent – a similar story across the country’s many other sectors – to fill the back-room vacancies left by male staff who’d enlisted (although they were expected to leave once the men returned). This pattern repeated in World War Two – and by the war’s end in 1945, women made up around 31 per cent of the bank’s staff.

It’s hard to fathom that at this time working women across Australia were still expected – by law – to leave work once they were married, the assumption being that a husband would provide for his family and working women should give up roles that could be held by men. (Women could also not get a bank loan without the sponsorship or guarantee of a man).

I’m always astonished when I read anecdotes in the bank’s archives of women staff who hid their marriages to keep their jobs, taking off wedding rings before slipping into the office, until the end of the ‘marriage bar’ in 1966.

Another major breakthrough for women’s equality in the bank came in 1978 with the appointment of its first female branch manager, Helen Lynch, who had joined the bank in 1959.

From early in her career, Lynch had argued not only that women’s abilities should be recognised, but they should be paid the same salaries for the same work as their male colleagues. When she joined, this applied to only three positions – staff training lecturer, international travel consultant or mechanisation officer – and Lynch made a point of filling all three positions. While, thankfully, the pay gap has markedly improved at the bank, across all sectors in the country, women's average weekly earnings are still 14.2 per cent less than men’s, according to the Workplace Gender Equality Agency.

After her appointment as branch manager in Rockhampton, Lynch went on to become Westpac's first female general manager and first executive in 1984 – the same year as Australia introduced the Sex Discrimination Act to protect people from unfair treatment due to their sex.

She was also a prominent advocate for women’s equality, founding Chief Executive Women in 1985, the national advocacy organisation whose most recent census shows despite progress over past decades, just 6 per cent of the top ASX300 companies had women CEOs in 2021.

Of course, underlying the march towards greater equality in workplaces has been incremental shifts in employment policies and laws – one prominent area being paid parental leave. Westpac introduced this in 1995 (led by great gender equality advocate and group executive at the time Ann Sherry, and backed by then chief executive Bob Joss), an industry first which inspired similar policies across both the private and public sectors.

There’s no doubt it has been a long road towards equality for women in Australian workplaces – and in many instances women (and men) employees throughout Westpac’s history have played a big role in pushing the national agenda forward.

But there’s still some way to go, and as more corporate like Westpac pledge to have women holding at least 40 per cent of the bank’s board and executive roles, it gives hope the march will continue.

I can only wonder what Edith Lamb and Tennyson Miller would make of how far we’ve come.