Steve Jobs to Buddhism: Pixar CFO’s own Toy Story

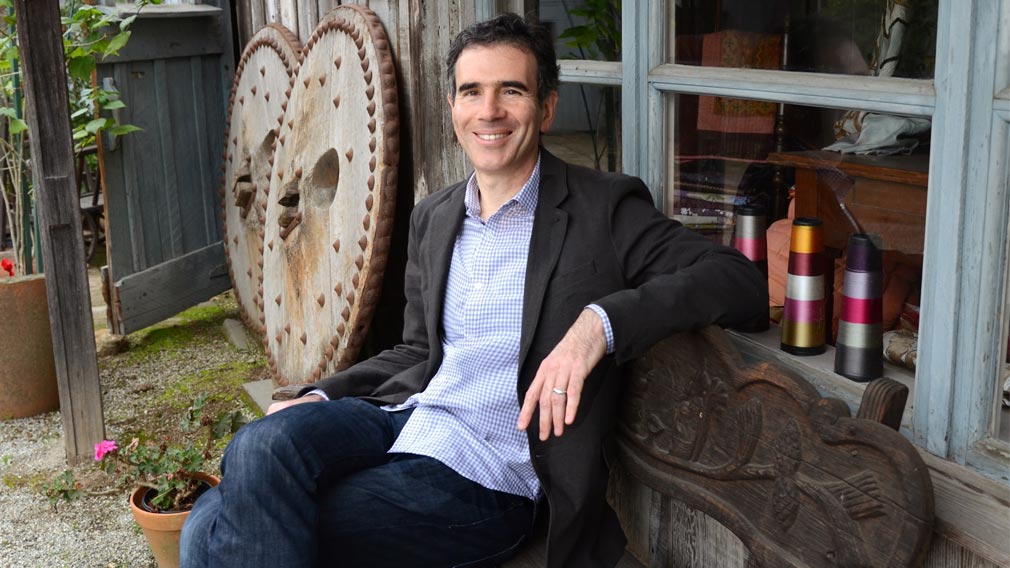

Lawrence Levy says Steve Jobs "understood what it meant to put aside personal agenda in order to analyse something and try to get to the best answer.”

As with most things in life, hindsight is beautiful when pondering disruption and technological change.

Even Lawrence Levy, a Silicon Valley stalwart and associate of the late Steve Jobs, struggles to predict which emerging technology or company will be the next to change people’s lives.

Virtual reality and augmented reality are two still “looking for a market”, he says. In contrast, he has more conviction on artificial intelligence, labelling it “the most obvious candidate for widespread disruption”, and also the power of commerce giant Amazon – an “efficiency machine” worthy of competitors’ concern -- ahead of its launch of full operations in Australia.

“It’s really hard to know. Most…things become disruptive when we look back at it,” Levy, the former chief financial officer of Pixar, told Westpac Wire in an interview last month ahead of his first trip to Australia.

“Search proved to be one of the most disruptive things. But I remember in 1995 when Pixar went public, Netscape, which was the original search company, also went public and people didn’t even understand what it was.

“(And) In 2002-03, we could have been chatting about all these new kind of blogging sites that were being set up, it didn’t look like a big deal. And then this other one comes along called Facebook.”

Levy is no stranger to the challenges of making a business out of innovative technology. Joining Pixar in 1994 at the request of Apple co-founder Jobs, he discovered that even though it had taken the next steps toward 3D computer animation and had masses of talented people, the company was burning cash and struggling to find a market.

Levy, who teaches meditation and has a passion for eastern philosophy, says one of the biggest issues was solving the tensions between the creative sides of Pixar’s operations and business realities, a problem he sees as still the greatest struggle start-ups face and why so many fail.

“You can have the greatest 3D animation software in the world but there’s like 20 companies that will use it,” he recalled of Pixar, which was a loss-making graphics company when he joined. “But when you’re a small company you have to sort of take big bets. You can’t hedge your bets and the only shot that I could see was to try to make something work in animation because at least there was an upside if you could make a hit film.

“That first film needed to be a (hit).”

Luckily, it was.

Finn McMissile, Lightninh McQueen and Mater from Pixar's 'Cars 2', roll into Bob's Big Boy for a pitstop in California, 2011. (Getty Images)

In late 1995, Pixar and Disney released Toy Story, one of the most successful animated box office hits of all time that spawned multiple sequels and ongoing merchandise sales. “If that (Toy Story) hadn’t happened, the rest would have been history and it wouldn’t have been a good history,” Levy quips.

As is often the case in many industries, Pixar’s rise after Toy Story proved painful for leader The Walt Disney Company, which had for decades delighted viewers with 2D hand drawn cell animation and characters such as Mickey Mouse and Bambi. Disney ultimately bought Pixar for $US7.4 billion a decade later in 2006.

“It was inconceivable to the Walt Disney Company that another company might unseat them in animation. Yet in the course of five or seven years, two companies unseated them (Pixar and Dreamworks),” recalled Levy.

“And that was on the strength of that technology so within the film industry it proved to be very disruptive.”

At a time when the Australian government is aiming to make the nation a “hub” for fintech and innovation in the region, Levy says his strong collaboration with Jobs meant where Pixar was located wasn’t critical to its success.

But these days he says it can be a factor, noting that start-ups benefit in tech meccas like Silicon Valley from the established “infrastructure”, such as access to capital, talent and experts well versed that enable a handful to succeed, but many more to fail.

“I know there are many parts of the world that really are interested in start-up culture and what it takes to do that and I believe its about putting all this pieces in place to make the environment rich,” says Levy, who is based in Palo Alto, California.

“You can’t legislate a successful start-up. You have to create an environment, start 1000 companies and see which one makes it. And I used to say the same in the film business. You can’t legislate a hit film.

“Start-ups are the same and so the richer the environment you have for fermenting these sort of seedlings then the more likely some of them are going to grow up into tall trees and that’s what you have in Silicon Valley.”

The Pixar logo at the main gate of Pixar Animation Studios in California in 2006. (Getty Images)

Several tech titans have emerged out of Silicon Valley in the past decade, many of which have grown into some of the largest publicly listed companies by market value known as the “FAANG” stocks (Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix, and Google) that has spurred talk of another tech bubble.

Having worked through the “dot.com” bubble of the late 1990s-early 2000s and observing the rampant mortgage lending in the lead up to the global financial crisis, Levy says some pricey stocks are far different.

“Just mere overpriced stocks themselves I think isn’t a bubble per se, it’s what’s the underlying thing is that’s a bubble,” he says.

“So you look at the health of the main companies, Apple, Google, Facebook, a bunch of others -- they’re actually thriving, doing really well. So there may be a correction but I don’t know if that’s a dynamic bubble.”

After expanding abroad to the UK and Canada, Amazon has Australia in its sights for an on-the-ground operation that experts believe could prove painful for incumbent retailers and shopping centre landlords. Macquarie’s equity analysts last week predicted Amazon could build a roughly $14bn business in Australia by 2025, assuming it snares 25 per cent of total online sales, similar to other foreign markets.

Levy says the key to Amazon achieving the difficult task of succeeding in new industries is its efficiency. He agrees with predictions of potential serious disruption to the retail sector similar to Walmart’s impact in the US decades ago, noting there’s been immediate improvement at his local Whole Foods store since Amazon’s recent purchase of the bricks and mortar food retailer.

“The thing about Amazon which is kind of like both amazing and worrying at the same time, they are like an efficiency machine. I don’t know how well they’ll execute on this of course in Australia, but they bring a daunting amount of efficiency to the markets they enter,” he says.

“Some might say it’s a good thing in terms of making products more readily available at lower prices but it’s also a daunting thing to compete with.

“You go back 40 or 50 years and look at Walmart and its impact on American retail industry was also enormous and Amazon is kind of a goliath like that and they’re really good at what they do.”

In Australia to promote his first book and speak at events, Levy says one of the biggest learnings from his roughly seven years in Pixar’s executive team was the power of collaboration from working with Jobs.

Another was the challenge in the corporate world of people being “imbalanced” and “one dimensional” in their lives. After leaving Pixar, he co-founded the Juniper Foundation, a Silicon Valley not for profit focused on bringing Buddhist teachings and meditation into contemporary life.

He says corporates can benefit from the “middle way”, a philosophy aiming to find a balance between people’s “bureaucratic” and artistic or free spirit selves.

And his biggest learning from Jobs?

“What I discovered with Steve was…the power of collaboration,” he says.

“When you can really unabashedly have two people or a group of people that can really air with each other and iron out and examine something with the intent of just sort of trying to get to the right answer rather than trying to win or be correct or something like that, then it’s very powerful.

“And I think this is one of the less understood things about Steve which is that even though he has this reputation as being this sort of hard charging, mercurial kind of businessman and he had characteristics like that, he understood what it meant to put aside personal agenda in order to analyse something and try to get to the best answer.”