Solving heart disease and banking headaches

Hesham Badr, a PhD researcher at Sydney University, is taking part in an Australian-first STEM PhD program jointly created by Westpac and the Group of Eight. (Emma Foster)

Two days each week, Hesham Badr investigates how to limit the number of open heart surgeries endured by children with congenital heart diseases using 3D printing technology.

The other three days, he works at Westpac.

In another division, Karina Mak spends part of her week using her skills as a psychologist to consult on how to better embed risk culture in the bank’s audit processes, and the rest of her time researching the effect of the “imposter phenomenon”.

The pair’s somewhat unusual working weeks and backgrounds defy the stereotype that banks are full of accountants, tellers and economists. They also reflect how corporates are seeking out staff with different perspectives and problem-solving skills while trying to work more closely with academia.

“Because I have a biomedical engineering background, I might take a different angle rather than a conventional banking view, which might spark a new solution. And that’s what the bank is looking for,” says Badr, a PhD researcher at Sydney University who is taking part in an Australian-first STEM PhD program jointly created by Westpac and eight Australian universities known as the Group of Eight.

Badr and Mak were among eight scholars with a focus on science, technology, engineering or mathematics – known collectively as STEM – selected for the four-year program, which has seen them working part time at the bank since February while continuing their ground-breaking academic research.

Sandra Casinader, Westpac’s head of HR strategy and research, says the program is unlike any the bank has seen and grew from the recognition that STEM capabilities are vital to the future.

“We knew that we have a dire need for more STEM capabilities across the bank and that diversity of thought is a critical part of our business success as we face into the future,” she says.

“We’ve addressed those needs in a unique way by recruiting eight talented, highly driven individuals who bring new ways of problem-solving. At the same time, we’re supporting them to deliver great academic research outcomes that will benefit Australians more broadly.”

She says the program is among a number of initiatives backed by Westpac to encourage a greater push towards STEM-focused education in Australia and closer ties between industry and academia, two areas experts say are needed to address the nation’s sliding ranks in global innovation indices.

Just last month, the 2017 Global Innovation Index released by INSEAD, Cornell University and the World Intellectual Property Organisation, saw Australia slip four places to 23rd in the world. If you dig deeper, the index puts Australia at 30th place for outputs and commercialisation, 52nd for innovation linkages and 48th for knowledge absorption.

Badr says that his desire to help address this slide was another reason he applied for the STEM PhD program, knowing that he may acquire new skills to help deliver faster results and get an insider’s view about what works in commercialising ideas.

When wearing his academic hat, Badr is working with teams at Sydney University and Westmead Children’s Hospital towards a “tissue engineering” solution to help children born with congenital heart diseases.

“The idea is that if a child has, for example, a defective artery, we would use 3D printing to build a ‘scaffold’ and surgically insert it into the body in place of the artery. The body would regenerate around it, forming cells to cover the scaffold and, over time, the scaffold degrades, leaving behind the child’s own cells and tissue,” he says.

“That way, the child shouldn’t need another surgery. What happens today is that children generally outgrow whatever material you use – if you put in a prosthetic implant, you’d have to have another surgery to extract it and put a new one in as the child grows.

“You really don’t want to have more than one open heart surgery in a lifetime, especially children.”

In stark contrast, at Westpac Badr is working in the group strategy team on a project to simplify digital banking services for institutional customers. He spends much of his time analysing customers’ feedback to get to the bottom of what they really need.

His manager at Westpac, Julia Patterson, says Badr brings additional analytical rigour to an already fairly diverse team, many also with STEM backgrounds.

“We didn’t necessarily want a particular skill in our student. We wanted a really smart person who could help us look at data and think about how to solve problems differently. Hesham has a heavier focus on data analytics than we already had in the team. He’s a good fit and I think we can give him a great experience,” she says.

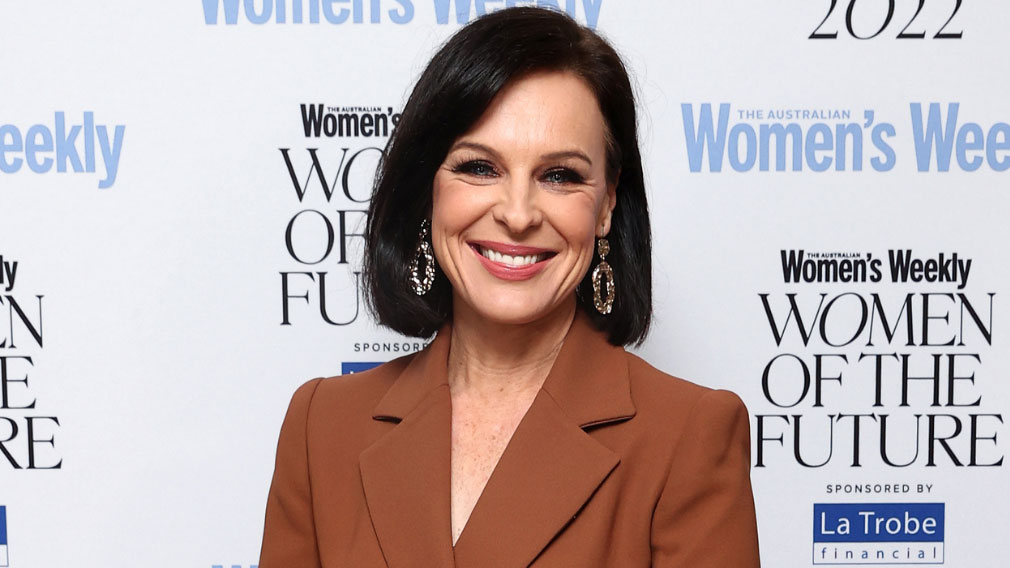

Karina Mak is researching the “imposter phenomenon” for her PhD, while consulting Westpac part-time on how to better embed risk culture in the bank’s audit processes. (Emma Foster)

Mak says she was initially surprised that her skills as a registered psychologist led to her being matched into a role in the bank’s audit team.

Her PhD sees her researching how careers are impacted by the “imposter phenomenon” – a notion that gained popular attention in best-selling book, Lean In, by Sheryl Sandberg, where high achievers attribute their success to luck, rather than their own intelligence, and often fear they’ll be uncovered as frauds.

“Financial services organisations are under the regulatory spotlight in relation to whether the climate within an organisation fosters positive risk management behaviours. That’s where my skills come in – to look at different approaches to measure and monitor people’s risk behaviours,” she says.

Mak’s manager Craig Duker adds that Karina’s lens is helping to strengthen the audit function by supplementing the traditional accounting and risk management insights of the team.

Casinader says that while it’s still early days for the STEM PhD program, initial feedback from all participants has given her confidence to start exploring how it may take shape for a future intake.

And the good news for those who may be affected by congenital heart disease, Badr believes solutions are close.

“I would say in five years there will be a product out there. It’s very promising.”