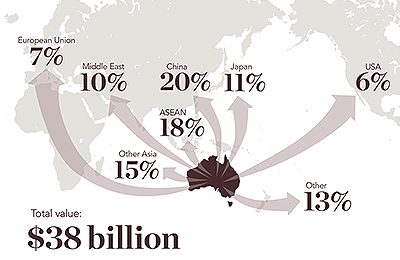

Promising markets

The Australian agriculture sector is on the threshold of change as new markets and competitors emerge across the globe.

The Australian agriculture sector is on the threshold of change as new markets and competitors emerge across the globe.

Words: Dana Worth

Australia's reputation as a global leader in agriculture is consistently reinforced by our diversity of clean, high-quality produce and our ready uptake of innovative technologies.

However, the stubbornly high Australian dollar makes this country a high-cost producer, and new, lower-cost rivals are emerging across the globe. Devising a strategy to secure our position and prosperity for the future is a necessity. Given the current fluctuations in the global economic climate, it's worth taking a look at the state of global agriculture and where Australia stands in comparison with the rest of the world.

Who are our rivals, old and new? What are their competitive advantages, apart from cost? How useful are trade agreements, and where are our most promising markets?

In early July, Australia signed what federal Minister for Trade Andrew Robb described to the ABC and Sky News as "the best deal Japan's done with anyone" and "the most ambitious trade agreement that Japan has ever done with any country".

Australia's deal with Japan is formally known as an Economic Partnership Agreement. The term is a Japanese preference over the Australian preference for 'Free Trade Agreement'.

Tony Mahar, General Manager Policy and Manager Economics and Trade at the National Farmers' Federation, observes that it would be a better term for all the so-called free trade deals we sign that result in improved-but not free-access to another country's markets.

Back in the 1990s, global agricultural exporters such as Australia pinned their hopes for better market access on the global negotiations coordinated by the World Trade Organization. But as round after round of these multilateral negotiations achieved so little, and were so achingly slow, one disenchanted country after another abandoned the multilateral catchcry, falling back on a patchwork of bilateral agreements. Bilateral trade negotiations, too, take years to conclude and may often achieve little. But at least they have the advantage of being fine-tuned to the expectations of each partner.

International trade agreements: threshold of a new era Australia is now negotiating agreements with China-without doubt our most important agricultural market for the future. We are also negotiating with the emerging markets of Indonesia-a large population that's even more accessible, geographically, than China-and India.

The agreement with India is expected to be particularly complex, as India has the capacity to become a direct competitor with Australian agriculture as the country further develops its beef and cotton production. What these countries want is likely to be a very big deal, indeed, as Australia seeks to raise the percentage that agriculture contributes to our GDP.

As a single category, agriculture, forestry and fishing's share of GDP has been hovering between 2 and 3 per cent for the past 10 years-a decline from 4 per cent in 1983 and a long way from the 20 per cent it held up to the mid-20th century. The decline of the sector's relative importance has not been due to falling output but to the rise of manufacturing's contribution to GDP.

Now, however, we're looking at a radically different future. As manufacturing share starts to diminish-the decline in its share of GDP has already started-there's a renewed government focus on agricultural policy.

According to the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (ABARES) 2014 paper 'What China Wants', China's demand for agrifood products is projected to double between 2009 and 2050.

'The real value of beef consumption in China is projected to rise 236 per cent, dairy consumption 74 per cent, sheep and goat meat consumption by 72 per cent and sugar consumption by 330 per cent, albeit all from a relatively low base when compared with developed countries. With the exception of dairy products, this projected rise in the real value of consumption is principally attributed to an increase in the quantity demanded, rather than a significant projected rise in real prices," the paper reports.

Without a clear agreement, says Austrade Trade Commissioner in Beijing, Susan Corbisiero, the situation in China can be confusing. Limits on primary produce market access can be haphazardly applied, and then there are other products, such as kangaroo meat and pork, which have no market access. Australian wine, however, is a huge seller.

Meanwhile, ABARES predicts that wheat imports into member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), led by Indonesia, are projected to grow-increasing on 2007 levels by 40 per cent in real terms-to reach nearly $4.25 billion by 2050. ASEAN member states sourced the bulk of their wheat imports between 1990 and 2012 from Australia. Indonesia's beef imports are projected to be the highest in the ASEAN area, reaching US$1.3 billion by 2050.

The one fact standing in the way of general optimism about Asia's rising consumption of Western-style foods is Australia's status as a high-cost producer. While some of our peers have formed innovative joint ventures abroad, such as the New Zealand-China Free Trade Agreement, which enabled New Zealand dairy giant Fonterra to establish joint ventures with Chinese dairy producers, offshoring production isn't the shoo-in for Australian agriculture that it might be for manufacturing.

It seems the renaissance of Australian agriculture is dependent on successfully targeting those affluent consumers who are committed to assured and high-quality produce.

The next few years will see global agricultural production remain firm, although expanding at slower rates, according to the 'OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2014-2023' released by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations. The report predicts that production growth will come mainly from developing countries in Asia and Latin America, both low-cost competitors, and that Africa and Asia will increase their net imports to meet their growing demand.

According to PwC's Sydney-based Agribusiness Leader Craig Heraghty, countries around the Black Sea, such as Russia, Ukraine and Turkey, which, like Australia, tend to have opposing climate cycles to those from Canada and the US, are shaping up as important wheat competitors.

"As they further develop there's potential for future growth," says Heraghty.

"But with grains you have to think about what the end use is. More grains are now used for livestock feed. Brazil has successfully converted to soybean and corn, but our climate is not conducive to large-scale soybean and corn [production]."

The advantage for Australia is that while South American countries are converting to feed grains, their meat production, particularly beef, hasn't grown as fast. And our beef is destined for a big future in Japan and South Korea under the new trade agreements.

One of the most significant new developments identified by Heraghty, however, is the relaxation of agricultural production quotas in the European Union. "That might turn European countries into exporters," he says.

"At present, you get penalised if you produce more than your quota. It's high-cost at the moment. But production of dairy from Ireland, for example, could rise 50 per cent in the next five years."

And then there's Africa. "Australia does export to Africa, but people are coming to understand that for the world to respond to the food crisis we need Africa. It's growing. There are really interesting developments there.

"One of the world's largest alcoholic spirit makers, Diageo, produces all its spirits for Africa in Africa, and sources some of the grains, such as barley, from Africa," says Heraghty.

As global agricultural export competitors emerge, Australia must go beyond the trade deals that are the focus of its current strategy.

We need to find innovative and ongoing ways of working within target countries to foster good relationships. We also need to invest heavily in ramping up our already superior standards of produce traceability.

The Australian Government is preparing to release its 'Agricultural Competitiveness White Paper' late this year, which will outline a plan to make Australian agriculture more competitive. When submissions were requested earlier this year, more than 660 were received by the mid-April closing date. There is huge domestic interest in this white paper, as it offers a chance to create a more coherent industry that will contribute positively to the restructuring of the Australian economy by boosting agriculture's contribution to GDP.

Heraghty points to two government-assisted initiatives that Australia might emulate. One is American investment in milling technology in China, which has made American red wheat more acceptable to Chinese millers than our premium hard wheat. The other is the ubiquity of New Zealand dairy giant Fonterra in China, which was assisted by top-level government-to-government contacts. Much of this kind of work is done through high-level networking and coordination of New Zealand's domestic production.

Bill Pritchard, Associate Professor in Human Geography at The University of Sydney, thinks one deterrent to a more coordinated approach in Australia is the difficulty that potential agricultural collaborators have in obtaining exemptions from the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC).

Australia's inherent competitive advantage in agriculture is a truth that is universally acknowledged, but concerned critics of the industry status quo say that farming is too fragmented, and that successive Australian governments have lacked clear long-term strategies to boost specific exports in key markets.

But the enthusiastic response to the government's call for written submissions to its white paper shows an Australian farming sector that is confident in its efforts to be an efficient producer of safe commodities that have already given 'brand Australia' the stamp of quality.

Now it's the government's turn to ensure that the vigour of the farming sector is sustained through excellent policy in a challenging new century.

Top Exports (AU$ Value, 2012-13)

Soybeans and soybean meal: $28.6 billion

Wheat: $11.1 billion

Dairy: $7.1 billion

Corn: $6.8 billion

Source: apps.fas.usda.gov/gats

The US mainly competes with Australian beef and wheat exports in the global market. The US also imports Australian beef. According to ABARES statistics, Australia's main exports to the US in 2012-13 were meat and live animals ($1.3 billion) and wine ($483 million). The US maintains a high level of farmer assistance and has recently made its taxpayer-underwritten crop protection insurance more generous. This provides compensation when crops fail and is also available for export pricing shortfalls.

Top Exports (AU$ Value, 2012-13)

Soybeans and soybean meal: $25.6 billion

Raw sugar: $14 billion

Poultry meat: $7.5 billion

Coffee: $6.6 billion

Source: atlas.media.mit.edu

Brazil is the world's number-one sugar producer and competes with Australia in the sugar and beef industries. The Brazil-Australia Strategic Partnership aims to increase bilateral investment flows in agriculture between the two countries. Brazil is currently protesting against the 2014 US Farm Bill's provision of cheap, taxpayer-subsidised crop insurance to American farmers. Brazil benefits from extremely low labour costs and offers farmers little by way of subsidies.

Top Exports (AU$ Value, 2012-13)

Dairy, including cheese & milk powder: $12.4 billion

Meat & edible offal: $4.8 billion

Fruits & nuts: $1.3 billion

Fish: $1.2 billion

Source: nzte.govt.nz/en/invest/statistics

New Zealand is the world's largest exporter of dairy and sheepmeat, and competes with Australia in these areas. It does not provide farmer assistance in the form of export subsidies, but the New Zealand dairy industry has a big advantage in the private cooperative Fonterra, which coordinates the industry by keeping it streamlined and export-fit. Fonterra's good working relationship with the New Zealand Government has helped it form collaborative relationships in overseas markets, notably China.

Wool & animal hair: $1.94 billion

Wool & animal hair: $1.94 billion

Cotton: $1.73 billion

Hides & skins: $842 million

Beef: $722 million

Beef: $1.43 billion

Beef: $1.43 billion

Animal feed: $377 million

Cheese & curd: $372 million

Wheat: $356 million

Wheat: $1.19 billion

Wheat: $1.19 billion

Sugars: $363 million

Live animals: $302 million

Cotton: $195 million

Beef: $788 million

Beef: $788 million

Sugars: $403 million

Wheat: $317 million

Cotton: $134 million

Wheat: $455 million

Wheat: $455 million

Crustaceans: $380 million

Cotton: $82 million

Cereals: $67 million

Oil seeds/fruits: $1.12 billion

Oil seeds/fruits: $1.12 billion

Wool & animal hair: $262 million

Beef: $201 million

Fruits & nuts: $159 million