Catch of the day

A look at Australia’s wild-catch and aquaculture operations reveals an industry that’s successfully navigating the rapids of reform to produce some of the world’s cleanest seafood.

A look at Australia’s wild-catch and aquaculture operations reveals an industry that’s successfully navigating the rapids of reform to produce some of the world’s cleanest seafood.

Words: James Anderson

The future is optimistic for the Australian fisheries industry. While trend lines charting the value of the industry over the past decade suggest steady decline, Australian fisheries is now in a unique position to capitalise on its natural advantages, thanks to recent reforms in the wild-catch sector and investments in aquaculture research and development.

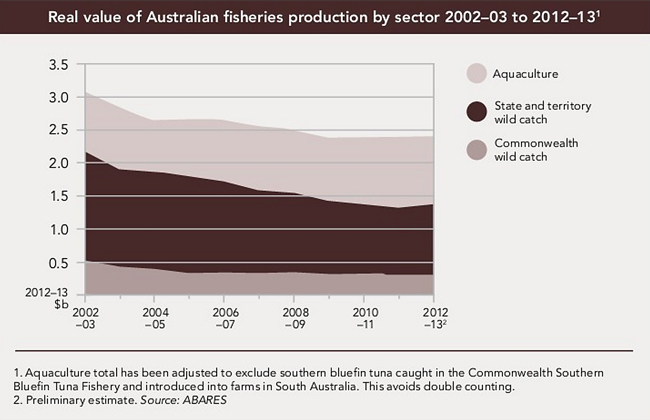

In 2002-03, Australian fisheries was worth $3.1 billion in today's terms, but underwent steady decline in value to about $2.4 billion in 2009-10, and its value has remained around there since.

A declining trend isn't unusual in the wild-catch sector, which has overreached biological limits in many parts of the world, but aquaculture is a sector that is experiencing great global growth. The Earth Policy Institute calculated that:

"In 2012 global aquaculture production overtook global beef production for the first time, reaching 66 million tonnes compared to beef's 63 million tonnes."

Australia barely holds a stake in this worldwide phenomenon, as our strict production and environmental regulations labour to compete with the vast, low-cost aquaculture enterprises of Asia.

Nevertheless, aquaculture was still responsible for 34 per cent of Australian fisheries production in 2013-14, according to the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (ABARES) 'Agricultural Commodities' report released March 2015.

Australia has many unique natural advantages that should predict a bright future for fisheries. And, along with hundreds of thousands of hectares of coastline suitable for aquaculture, we also have some of the world's best aquaculture scientists.

Australia has many unique natural advantages that should predict a bright future for fisheries. And, along with hundreds of thousands of hectares of coastline suitable for aquaculture, we also have some of the world's best aquaculture scientists.

Among them is Dr Nigel Preston, Research Program Director of CSIRO's Integrated Sustainable Aquaculture Production program. Preston believes that with the right policy settings, protein production from Australian aquaculture could theoretically rival animal protein production on land.

That may not be the reality for some time, but the hope is not futile. Australia's strict environmental controls have produced some of the world's cleanest fish farms and the sector is recovering after a period of stagnation.

In the NT, the $1.45-billion Project Sea Dragon is set to change Australian thinking about the scale of aquaculture with a 10,000ha prawn farm producing 100,000t per year. And the Tasmanian Atlantic salmon sector, worth $500 million a year and already Australia's most lucrative fishery, has permission to expand into Macquarie Harbour, a move that will double production and, presumably, value.

Looking at wild catch, the sector has spent the past 15 years working through reforms designed to rebuild overworked fisheries, introduce quota management and create tradeable fisheries rights. The sector has also been challenged by the difficult trinity of a high Australian dollar, high oil prices and a shortage of manpower-largely driven by the resources sector, according to Austral Fisheries' CEO, David Carter.

But the situation has improved, along with Australia's competitiveness in the seafood export market. The Australian dollar has fallen, oil prices have fallen, the resources sector has scaled back its demands on manpower, and the reform process is fundamentally complete, state regulatory quirks aside.

The wild-catch sector is working with rebuilt fisheries that are protected against another run-down, with sustainable operator numbers and secure rights-ingredients that Carter says have rekindled investor interest in the industry. That includes his own company, which sees enough clear water ahead to start replacing 30-year-old boats.

Nevertheless, there's still some distance to go, says Stuart Richey, who runs Richey Fishing Co Pty Ltd out of Shearwater, Tasmania, and was recently appointed Chair of the Australian Maritime Safety Authority Board.

"The so-called super-trawler, the factory trawler that's here now - that is the perfect example of what should be happening," he says. "She's a foreign ship that's brought in to do a job; she's catching Australian quota under Australian conditions, Australian monitoring, very strict regulations and quota management."

Australian fisheries now sees the way clear to stake a much more profitable claim on hungry global markets such as China, Hong Kong, Taiwan and Vietnam, which together imported 66 per cent of our total exports, worth $836m, in 2013-14.

Australian fisheries now sees the way clear to stake a much more profitable claim on hungry global markets such as China, Hong Kong, Taiwan and Vietnam, which together imported 66 per cent of our total exports, worth $836m, in 2013-14.

There's also room to reclaim some of the huge domestic seafood market.

"Australians have always taken the 'Scotch fillet steak' of fish stocks - abalone, rock lobster, prawns, blue-eye trevalla, ling and flathead," Richey says, "and they've never eaten the 'sausages' - Australian sardines, mackerel, red bait and some tuna species such as skipjack.

"The more we read about healthy eating, the more we see that we should be eating those bottom-of-the-food-chain fish. We have very large stocks of those species and we need to value-add them."

Which, he adds, is exactly what the visiting Dutch super-trawler is doing in cooperation with an Australian company.

Broadly, Richey sees the Australian fisheries sectors segmenting into three distinct parts. "I see aquaculture becoming more like the chicken industry, where farmed fish becomes a staple," he says. "Every single day of the year there will be fresh Atlantic salmon or fresh barramundi in the marketplace."

He sees wild catch becoming two sectors: a yet-to-be-developed market for secondary fish, and the current catch of prized fish mainly for the restaurant trade.

Carter's Austral Fisheries has already positioned itself firmly in the latter market. A pioneer of the Patagonian toothfish fishery in sub-Antarctic waters, Austral now has 71 per cent of the toothfish quota.

To properly capitalise on the position, and the prized fish, it has begun shifting its output from "bodies in bags" to a high-end branded product with the help of celebrity chef Neil Perry.

As a bag of fish, toothfish sells for US$25-26/kg. But as 'Glacier 51 Toothfish', sold to restaurants as 3.5kg sides, vacuum-packed against a black background, it sells for US$65/kg.

"A big draw for us putting a brand on our fish is the social licence it gives," Carter says. "We needed a conversation with an Australian support base that made us relevant."

As he's discovered, having a social licence to operate isn't just about community approval. It also gives a business permission to ask more for its product, and that's going to be vital for Australia's high-cost fisheries in a market awash with low-cost options.